This article first appeared in Skeptical Inquirer 31:2 (2007), 58-63

Reproduced with permission

In the context of non-standard claims about the remote past, the fields of religion and language are both highly significant but might superficially appear largely unconnected. However, there are a number of cases where religious and linguistic issues are intertwined. In fact, this is not entirely surprising: both religion and language are core elements in human culture and thought, and language is both a determining factor for human thought and its most articulated vehicle of expression. More specifically, many human groups regard their language as an identifying characteristic. Folk-linguistic beliefs often centre on the origin of the language, treated as a key aspect of mythological/religious accounts of the origin of the group and its world. Positions on the two fronts are thus frequently connected.

One instance of this phenomenon which is well known in ‘the West’ is the Tower of Babel story in Genesis. This Hebrew myth explains the diversity of human languages in terms of an initial state involving a single language being ended by divine intervention in the relatively recent past. Of course, this is quite contrary to the modern scientific linguistic position that humans have had language for at least 70,000 years and that diversification (and convergence) of languages has proceeded by way of ‘cultural evolution’ throughout this period. As one might expect, those who still accept the story as literally true are motivated by fundamentalist Jewish or Christian belief in the literal inerrancy of Genesis, ie they are ‘creationists’.

More surprisingly, some of these modern believers in the Tower of Babel are trained in linguistics. Around the world there are various branches of the Summer Institute of Linguistics. SIL trains linguists in fieldwork methods, so that they can analyse unwritten languages around the world, develop writing systems, prepare dictionaries and grammars – and translate the Bible into each such language, for this otherwise worthy enterprise is linked with Wycliffe Bible Translators, an arm of fundamentalist Christianity! Indeed, some of its qualified linguists and instructors are creationists. An example of their work is May 2001, which essentially upholds the Babel story. For a qualified linguist, May is remarkably ill-informed on historical linguistics and his summaries of orthodox views are wildly outdated. (This is of course often true of scientifically trained creationists.)

At a time when Genesis was generally interpreted as historical (which was before the development of historical linguistics), it was often assumed that the single pre-Babel language was Hebrew, the language of the Pentateuch. This idea is in fact far from dead. One current manifestation of it is the work of the Jewish creationist writer Isaac Mozeson (Mozeson 2000; also web site). Mozeson claims that virtually all the words of all languages derive from ‘Edenic’, which is basically early Hebrew with some (Proto-)Semitic roots not attested in Hebrew itself (Hebrew is a member of the Semitic language family). As is very common in such cases, the main problem with Mozeson’s proposal involves the methods of comparative linguistics which he adopts. These are long outdated and are now used only by fringe amateurs. The probability of pairs of superficially similar words in apparently unrelated languages having very similar or the same senses by chance is in fact much higher than Mozeson suggests. In this particular case most of the alleged correspondences between phonemes are unsystematic and arbitrary; each correspondence is invoked as it is needed to ‘explain’ specific forms, but there is typically no good explanation for why different correspondences apply in different cases, or even an admission that this is an issue that needs to be addressed. It has long been known that language change does not occur in this unsystematic way: there are often exceptions to a given pattern of correspondences, but these are relatively few, and where information is available they can generally be explained. Using the methods adopted by Mozeson and other amateurs, one can ‘prove’ (spuriously) that almost any two languages share large amounts of vocabulary. The statistics involved here have recently been formalised by Ringe (1992, etc) and other historical linguists, and while there is some debate about specifics the overall case is overwhelming.

In addition: in many of the cases cited by Mozeson, other etymologies are already known or proposed with good evidence. His theory also contradicts a large amount of well-grounded information about the ‘genetic’ relationships of entire languages (in language families). Further, the analysis ignores the fact that ‘genetic’ relatedness (as opposed to influential contact) always involves specific elements of grammar and phonology as well as shared vocabulary. In fact, it is clear from a range of major errors that Mozeson simply does not understand historical linguistics.

On a linked web site, Jeff Benner argues (implausibly) that Hebrew script, which was clearly partly pictographic in origin, kept its pictographic function even after it became alphabetic and that the Hebrew language and its script must have appeared simultaneously when God created Adam with a mature knowledge of the spoken and written language (another creationist). In support of the former claim he cites some fringe and semi-fringe writers, notably Fano (1992), who was one of the members of a mid-C20 breakaway Italian school of non-scientific linguists influenced by the idealist philosophy of Croce (1902, etc). Fano in fact rejected Croce’s more extreme ideas, but remained conspicuously non-mainstream in international terms.

Another fairly similar project is that of ‘Britam’, a British-Israelite-like group led by Yair Davidy; but this group (naturally) focuses on alleged linguistic parallels between Hebrew and the Celtic languages specifically. The parallels presented again lack conviction, for the same reasons and also because of reliance on outdated sources. See eg Davidy nd (etc), Davidy’s journal Tribesman, works such as ‘Britam’ 2001 and the Britam web site. In the same way, the British Israelites proper implausibly proclaim linguistic connections between Hebrew, on the one hand, and both English and Welsh, on the other (see eg James nd, Evans nd). British Israelite philology is especially bizarre. In recent times, the professional linguist Theo Vennemann (2001) and some relatively well-informed amateurs have actually argued seriously for early Semitic influence on Celtic, with better evidence; but even Vennemann’s case is regarded as dubious.

Another, perhaps more arguable proposal is set out in Blodgett 1981. Blodgett, a lecturer on German and Hebrew, argues that Hebrew exerted major influence on Germanic in antiquity through the dispersion of the ‘Lost Tribes’ of Israel into central Europe. He knows some historical linguistics (although there are several undergraduate-level errors which are quite damaging). But even his case for this relatively modest revision of history is simply not strong enough, in linguistic terms at any rate.

A different revisionist approach to the Old and/or the New Testament involves the relocation of the events described away from Palestine to some other quite distant area, or the suggestion that biblical figures lived at times in remote places. For example, Jesus is said to have survived his crucifixion and to have relocated to Kashmir or Japan, eventually dying there. There is a linguistic aspect to the version involving Japan, centering on a temple chant at Herai in northern Honshu where the ‘Grave of Jesus’ is exhibited (see also Mazza & Kardy 1998, Desmarquet 1993, etc). Bergman (on the web) claims that this chant is in fact in Hebrew, modified to fit Japanese phonology. It is also claimed that a document dating from around 100 CE and written in the kana syllabary (several hundred years before kana are known to have existed) exists in the area; this text allegedly shows that Jesus is indeed buried in Herai, and contains his will. But Bergman’s reading of the chant can be made to seem plausible only by very special pleading. In 20 minutes I devised a Latin reading which is closer to the Japanese phonetics than Bergman’s Hebrew is and also fits the situation better (‘Dark Age’ missionaries in Japan). The most plausible analysis is still that this is a normal Japanese folk-chant with some sequences that display accidental rather approximate similarities to Hebrew words. And the key document is probably a C19-20 forgery.

There is a long non-mainstream tradition of re-interpreting the events related in Exodus. Notably, Akhenaten and Moses are often linked or even identified as the same person or as closely related. Akhenaten’s dynastic (non-immediate) successor Tutankhamun is also involved. The main relevant work with a linguistic element is Sabbah & Sabbah 2002, which argues that the ‘chosen people’ were in fact the Egyptians, who were conquered by the Hebrews and suffered under the re-writing of history by the victors (a common tale and not an untrue one, albeit over-used by postmodernists and fringers). In this version, Moses was not Akhenaten but another pharaoh, Ramesses I (while Akhenaten was Abraham!). Predictably, there are many problems here; but the linguistics is especially weak. The Sabbahs write as if the origin and development of the Hebrew abjad (consonantal alphabet) and other related Semitic scripts were only very sketchily known, with large gaps waiting to be filled by researchers such as them. They derive the abjad from key parts of hieroglyphs, each retaining much of its Egyptian pictographic significance (compare Benner above).

However, by dynastic times the relevant Egyptian hieroglyphs had already lost this significance. The script was predominantly phonological; that is, each symbol, even if pictorial, now usually represented a consonant or longer sequence of phonemes, regardless of meaning. And the Semitic abjad scripts are undoubtedly closely connected with each other. There may well be an older Egyptian source for some of the Semitic letters; but, if there is, it is involves this whole family of scripts, not just Hebrew. In fact, the evidence for the specific connections proposed – even where the words themselves are or may be related – is mostly impressionistic. Many cases involve special pleading or outright contrivance. It is easy to find accidental parallels between Hebrew letters and hieroglyph-parts.

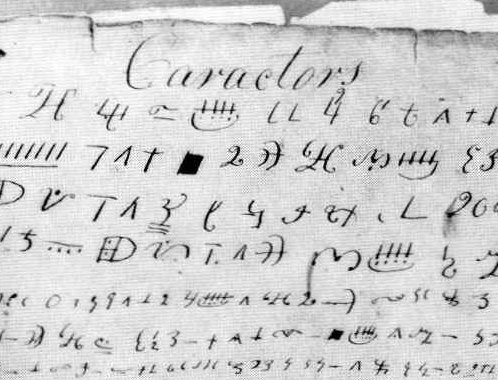

Another issue in this area is that of Latter-Day Saints sources (eg Larson 1992, Nibley 1988) continuing to promote the veracity of the ‘Reformed Egyptian’ in their Book of Abraham and other texts associated with The Pearl of Great Price. See Smith nd for the original account of this otherwise unknown language. When the early LDS leaders claimed that this was the language of the plates which the angel lent them to be mystically translated, very little was known about Egyptian, but nothing learned since has confirmed LDS ideas on this front. The small pieces of genuine Egyptian text presented in LDS sources were already known at the time and have subsequently been interpreted quite differently.

There are also LDS texts which seek to demonstrate the presence of languages and scripts used in ancient Israel in ‘inscriptions’ found in the Americas and to relate known languages of the Americas to Hebrew (eg Harris 1998).

In quite a different vein, Lucas & Washburn 1979 was something of a precursor to Drosnin 1997; in fact, there have been many such efforts to prove that the Bible or some other religious text is reliable by finding numerical and/or verbal patterns in the text which allegedly could not have come to be there by chance and which often carry important messages (prophecies, etc). The cases for these claims are typically much weaker in statistical terms than their proponents suggest (see the now familiar skeptical literature on Drosnin 1997). But what has not always been made clear is that in many cases their linguistics is also less than competent. For instance, Lucas & Washburn – misinterpreting a reference work – claim that there are no rules at all for the use or non-use of the Greek definite article, the equivalent of English the (they therefore claim that God was free to include the article or not in each New Testament phrase, in order to make the numbers add up). This is untrue.

Another writer who found hidden messages in the Bible was Max Freedom Long (1983, etc). Long met Hawaiian kahunas with supposed psychic powers and came to believe that Jesus had studied in an ancient Polynesian mystical tradition called Huna which had once prevailed in Egypt (he has some novel interpretations of hieroglyphs!) and elsewhere in the ancient world. Jesus and his apostles accordingly inserted secret messages in the texts of the Gospels, which are much more important than the overt message of the texts. These messages are in a secret language or ‘code’ which is the ancestor of Polynesian (and is still spoken by a tribe in Morocco!). Confusingly, Long’s specific claims often seem to involve current Hawaiian, not early Polynesian. He clearly did not know linguistics and his interpretations require large amounts of special pleading if they are to be deemed remotely plausible.

Again in a different vein, Maxwell et al. 2000 is inspired by the late C19 diffusionist writer Gerald Massey (1998, etc), who believed he could trace all religions back to a small number of linked cults (stellar, lunar, solar). Massey merged the genuine knowledge that was emerging from Egypt with the early modern fantasies – now largely debunked – about Egyptian mystery religions. Maxwell et al. focus mainly on the religious issues in the usual historical revisionist manner, finding a huge number of possible links but arguing persuasively for very few. However, they also present linguistic ideas taken from a three-volume work published around 1940, apparently anonymously (adding more examples of their own). This book has the overall title Priesthood of the Ills and contains a large amount of non-standard philology, adduced as support for these diffusionist theories of religion. The author believes that there is a Language Conspiracy, which involves (a) keeping humanity divided by enforcing the use of many mutually unintelligible languages and (b) blocking humanity from discovering the original (‘true’) meanings of words. This suggests that all changes in the meanings of words are illegitimate, which of course is nonsense. However, the author believes that the meanings of some of the key words in ancient languages were very different indeed from those of the English words normally used to translate them, and that this has been deliberately concealed by the forces of Evil. These ‘true’ meanings are implicated in huge numbers of unrecognised links between languages. These writers suggest that simply focusing on pronunciation rather than spelling will enable one to hear which words are really connected, because they sound similar! Once again, the last 200 years of historical linguistic scholarship is simply ignored.

As well as members of the Judaeo-Christian tradition, some Hindu believers also adopt non-standard views on language which relate closely to their fundamentalist religious views. These latter involve ‘Vedantic creationism’, including the belief that modern humans have existed for hundreds of millions of years (almost the reverse of the best-known brand of Judaeo-Christian creationism with its very short chronology). The most familiar manifestation of Vedantic creationism is Cremo & Thompson 1996 (archaeology and palaeoanthropology); for a critical review see Brass 2003. Books in this tradition that deal with more recent history uphold the traditional Hindu belief that India was the centre of Asia’s or Earth’s oldest civilisation, with culture diffusing from there in early historic times. These notions have a nationalistic and religious appeal for some Indians.

A common theme in this tradition involves the Sanskrit language, in which the Vedas (the most venerated Hindu scriptures) were written. The orthodox position is that Sanskrit was brought into India around 3,500 years BP as part of the European/West-Asiatic diffusion of the Indo-European language family from a base somewhere near the Black and the Caspian Seas (dated around 5-6,000 years BP). There is a serious case for the contrary view that the language was in India rather earlier and is perhaps represented by the undeciphered Indus Valley Script – see eg Bryant 2001 – though most of the linguistic evidence supports the standard view. (A generally accepted decipherment of this script – as representing Dravidian, IE, or another language family again – would be a very important factor in the resolution of this issue.) However, there is also a more extreme Indian tradition – see eg Sethna 1992 – upholding the truth of legends interpreted as placing Sanskrit in India much earlier (7-8,000 years BP, sometimes still earlier). Indeed, Sanskrit is said to be much closer to Proto-Indo-European than is thought by modern historical linguists, and in fact the usual fringe Indian claim is that IE actually originated in India and spread westwards. This extreme view is almost certainly wrong: it is clear that Sanskrit had undergone major changes of its own vis-à-vis Proto-IE, and was especially close to it only in some respects.

One recent manifestation of this belief system is Knapp 2000. Knapp’s book is considerably less scholarly than Sethna’s; it is also more accessible outside India. Knapp himself is a convert to Hinduism and a fervent promoter of all these ideas. He argues that Vedic ideas, together with the Sanskrit language, were once spread all over the Earth by a technologically advanced Hindu civilisation which provided the impetus for civilisations from China to Peru. Proto-IE – as distinct from Sanskrit – never existed. Indeed, Sanskrit is the ancestor not only of IE but of all languages! At a detailed level, Knapp and his sources make extensive use of language data by way of support for their historical claims.

However, most of Knapp’s linguistic claims are simply wrong. Like Mozeson, he proceeds by identifying superficial similarities between Sanskrit words on the one hand and words in other languages on the other, and deduces that the non-Sanskrit words are derived from the Sanskrit words (which he deplores; corrupted and perverted are among his terms). Most of these equations are simply asserted as facts, with no supporting evidence. But, as with Mozeson, there is in general no reason to accept them. At best they are undemonstrated and not especially plausible. And most of them are actually known to be invalid; the words in question are simply not connected but have established unrelated etymologies. One example involves the name Australia, which is a known modern coining transparently based on Latin, where it would mean ‘southern’ (land, etc). Knapp states that it is from Sanskrit Astralaya, meaning ‘land of missiles’; he suggests that the pilots of vimanas (flying vehicles reported as used by Hindu gods, here interpreted as actual aircraft) practised firing their missiles in Australia, thus creating the deserts! But once again Knapp is proceeding as if the tradition of serious historical linguistic scholarship did not exist.

Knapp is not the most extreme manifestation of this fringe tradition; that ‘distinction’ belongs to Gene Matlock. Matlock’s work (2000, etc) is about the diffusion of Hindu culture, the ‘true’ basis of Hinduism, and many features of the Sanskrit language to groups such as the Biblical Israelites, early Europeans including the inhabitants of the British Isles, and Amerindians (especially those in the SW of the modern USA and in Mexico). His procedures are similar to Knapp’s but ‘further out’. He knows virtually no linguistics and shows himself to be a believer in various non-linguistic fringe ideas. See Newbrook 2001 for a review of Matlock’s material.

Knapp and Matlock draw much inspiration and many examples from P.N. Oak, a now elderly writer living in Pune, India. Oak (1992, 1995) attacks the accepted etymologies for hundreds of English and other non-Indian words, place-names etc, and proposes new Sanskrit etymologies – most of them ludicrous both linguistically and historically. Like Knapp and Matlock, he gives no evidence for most of his etymologies, but merely invites readers to agree that they are obviously correct. Oak simply does not know enough about the subject or about the history of any language other than Sanskrit. Even for Sanskrit he uncritically adopts Vedic ideas about its vast antiquity: he thinks it was used in happy Hindu communities worldwide for 2000 million years [sic] until wicked Christians, scientists and such subverted all this and re-wrote history!

Other religious/quasi-religious groups with links with Hinduism, including some based in ‘the West’, also focus on Sanskrit. With aid from its supposed spiritual allies, the Aetherius Society (see web site) still forges ahead on its mission to save Earth from its extra-solar foes. It regards Sanskrit not merely as the ancestor of all human speech but as vastly ancient and the main lingua franca of a whole swathe of inhabited planets! Naturally the Theosophical Society also focuses on Sanskrit; Blavatsky’s ideas (Blavatsky 1982, etc) on the language and on linguistics, which were strange and dated even in her own time, continue to command respect.

There are also non-standard linguistic ideas associated with other traditional religions such as Australian Aboriginal and New Zealand Maori spirituality. In addition, there are further implausible claims along lines similar to those made in Priesthood of the Ills regarding the role of religious organisations in distorting the truth about linguistic history, eg the theory promoted in Nyland 2001 that during the ‘Dark Ages’ the Roman Catholic Church deliberately concocted most modern languages by distorting the Basque lexicon. This article has done no more than ‘scratch the surface’!