Vyse ♥ Cumberland

As one of the younger sons of George III, the Duke of Cumberland did not initially appear destined for great things: until his elder brothers died childless, when there seemed to be a possibility that Cumberland might be in line for the British throne … had it not been for the birth of a certain Princess Alexandrina Victoria, daughter of the fourth son of George III.

In the decades before that inconvenient royal birth, Howard Vyse’s father, General Vyse, descendant of a respectable and pious Church of England clerical family, had been Comptroller of the Household of the Duke of Cumberland; i archive correspondence attests to the cordial relationship between the two, ii and to the Duke’s help in arranging for the General’s only son, Richard – later Col. Howard Vyse – to sign up as an ensign in the 1st dragoons at the start of his military career. iii Moreover, at one time, the Duke had also been Colonel of the 15th King’s Light Dragoons, in which Howard Vyse’s own son, Richard, was later to become a lieutenant.

Clearly, the Vyse family had many reasons to want to acknowledge their gratitude to Cumberland. Vyse’s eldest son, George Charles Ernest Adolphus Richard, was perhaps called “Ernest” in honour of the Duke. Similarly, it is possible that his daughter, Augusta Elizabeth (1814-1879) was named for Cumberland’s sister, the Princess Augusta Sophia; in October 1840, Vyse attended her funeral. iv

Unfortunately, the Duke’s private and public life did not always proceed quite as smoothly as his ducal rank and royal status might have led one to expect. One night in May 1810, whilst asleep in bed at home, he was attacked with a sword; and, when the household was roused, it was discovered that Joseph Sellis, one of Cumberland’s two valets, was lying in a locked chamber with his head almost severed. v Eventually, it was concluded that, after attempting to murder his royal master, Sellis had committed suicide (although quite how was never explained). vi Despite this finding, the popular press had a field day, and the Duke found himself accused, not only of his valet’s murder, but also of adultery, bribery, buggery, burglary, robbery, sodomy, blackmail, and any other crimes that the press’s overactive imagination could come up with.

But it appears that Vyse refused to allow reports of shocking events to interfere with his relationship with his patron. In 1813, he became an equerry to the Duke; vii this was the same year in which Cumberland, having become embroiled in a political scandal in the seaside town of Weymouth, was packed off to Europe. There, the Duke fell in love with his cousin, Duchess Frederica of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. viii They married two years later; but the Duke’s mother, Queen Charlotte, who had opposed the union, refused to receive her son’s bride. Eventually, the couple moved to Germany, and did not return until the late 1820s, when only the young Princess Victoria stood between the Duke and the British throne.

It was at about this time that a senior civil servant made the following entry in his diary:

There never was such a man, or behaviour so atrocious as his —a mixture of narrowmindedness, selfishness, truckling, blustering and duplicity, with no object but self, his own ease, and the gratification of his own fancies and prejudices, without regard to the advice of the wisest and best-informed men or to the interests and tranquillity of the country.” So wrote Charles Greville, Clerk to the Privy Council, in his diary for 2 March 1829 and from its immediate context this unflattering description is generally supposed to refer to Ernest Augustus, Duke of Cumberland. ix

However, although it seems more probable that Greville was actually referring to King George IV, x it is safe to say that many people agreed with this opinion: Cumberland’s public image was that of a “monster of depravity.” xi On St. Valentine’s Day 1829, politician Thomas Creevey wrote about the Duke to one of his correspondents:

Are you aware that Captain Garth is the son of this Duke by Princess Sophia. General Garth, at the suit of the old King, consented to pass for the father of this son. xii

Princess Sophia was one of the sisters of the Duke of Cumberland, xiii who, besides all his other problems, was now being accused of incest; although this is now held to be nothing more than an offensive rumour, for Creevey was well known for his bias and inaccuracy. xiv But this did not prevent the inevitable circulation of lurid allusions to threats, blackmail and worse.

Only a few months after Creevey’s accusation of incest, the Duke’s image was tarnished by yet another scandal. The press circulated a story to the effect that, in July 1829, the Duke had tried to rape Sarah, Lady Lyndhurst (1795-1834), wife of Baron Lyndhurst (1772-1863), the Lord Chancellor: although it is now suggested that this likely blew up out of all proportion what was no more than a minor incident during a social visit. xv

The Monster of Depravity and the Damned Fiend

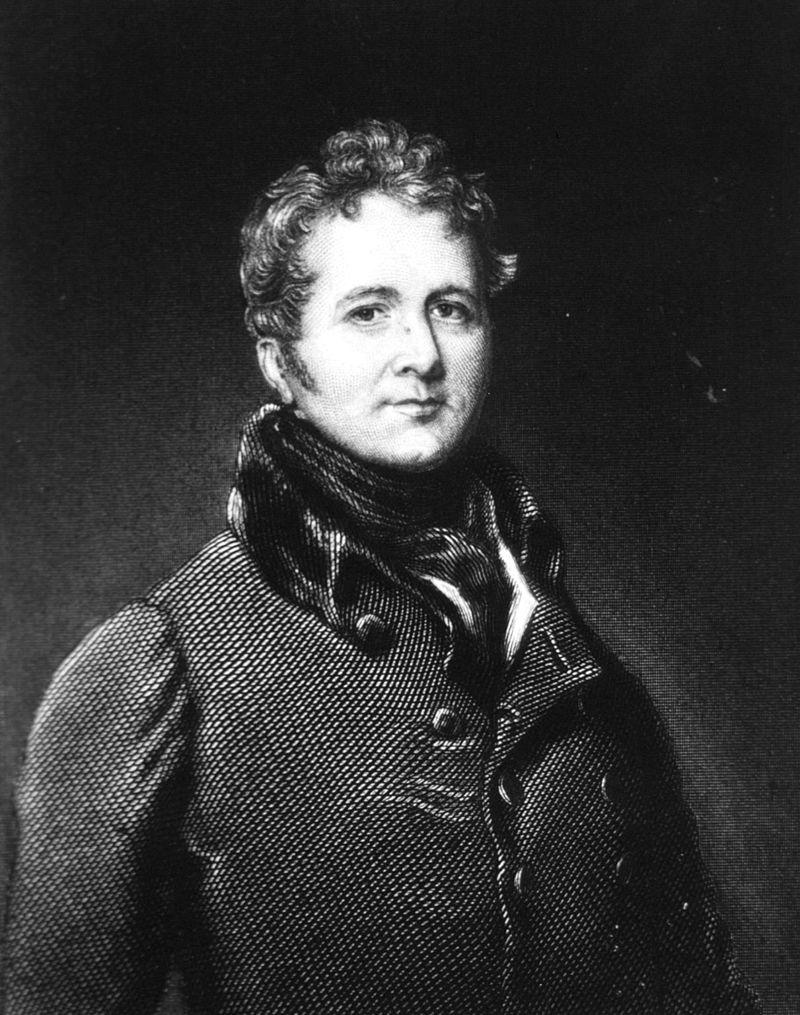

Before his death in June 1830, George IV had suffered a long illness. He was attended by physicians Sir Henry Halford (1766-1844) and Sir William Knighton (1776-1836); xvi and Knighton was also uncle to the King’s Chaplain, the Rev. John Seymour (1800-1880).

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:William_Knighton.jpg

In time, Sir William Knighton came to act also as the King’s private secretary, and wielded considerable influence over the ailing monarch, a state of affairs which did not necessarily find favour with everyone at Court. Cumberland seems to have done his urbane best to paper over any cracks in his relationship with his brother’s secretary, xvii but there were underlying tensions between the two, and, at one point following the Catholic Relief Bill of 1829 (which Cumberland bitterly opposed), the Duke made a claim (completely unfounded) that the Government would have fallen, but for the interference of “a damned fiend” – i.e., Knighton. xviii It is not known how much of this reached the ears of Knighton’s nephew; although it is difficult to see how the chaplain and his relatives could not have been aware at least of the main points of the situation.

The Duke’s reputation, meanwhile, continued to suffer further dents. A few months after the Lyndhurst affair of July 1829, he was accused (there were even satirical prints) of conducting an affair with Lady Mary Graves (1783-1835), a 47-year-old mother of twelve children, and wife to Lord Graves, Comptroller to the Duke of Sussex. For some weeks, Cumberland and Lord and Lady Graves tried to rise above the rumours. xix But, on 6th February 1830, after being sent yet more derogatory press cuttings about his wife’s supposed adultery, Lord Graves took his own life: xx a tragic circumstance which, needless to say, did not escape the notice of the press.

In the immediate aftermath of this affair, Cumberland apparently tried to visit Windsor to see the ailing King. But Knighton was bent on persuading the monarch not to allow any such meeting:

I went down to Windsor for the express purpose of recommending the King, if possible, to avoid seeing the Duke of Cumberland. Whatever might be his innocence as to intrigue with Lady Graves the public were in a state of mind not to believe it. The King, by seeing much of him would involve himself without doing any real benefit to the character of his brother. I succeeded in convincing the King that I was right, but only through the agency of [the King’s sister] the Duchess of Gloucester. xxi

A few weeks afterwards, Knighton was still trying to circumvent Cumberland’s efforts to see the King:

I this day saw the Dss [Duchess] of Gloucester—spoke of the Duke of C[umberlan]d & wish’d him away. xxii

Some months later, on 26th June 1830, the King died, and, apart from some clearing up of the late King’s affairs, Knighton’s work came to an end. xxiii William IV succeeded to the throne, and Cumberland found his influence now much reduced; xxiv the two men, though brothers, were divided by political differences, and the new King was also greatly irked by the scandals and controversies swirling round the Duke.

Montagues and Capulets

Unfortunately for George Vyse and Lizzy Seymour’s marriage prospects, several of the Seymours were not only related with the Knightons, but had also intermarried with them. The King’s Chaplain, later known as Sir John Hobart Culme-Seymour, was the eldest son of Admiral Sir Michael Seymour KCB, xxv and brother to diarist Richard Seymour. And, on 22nd June 1829, Knighton’s daughter, Dorothea, had married Michael Seymour, the Admiral’s son: relatives, in other words, of the very man who, in the eyes of the Duke of Cumberland, had actively sought to scupper his political aims, and had also headed off his attempts to visit the late King at a time when the Duke needed personal support over the Graves affair.

It is difficult to gauge how much of this Vyse would have known: but enough, perhaps, to lead him to believe, rightly or wrongly, that Cumberland would take a very dim view of any marriage alliance between Vyse’s own family and close relatives of the man whom the Duke suspected of trying to thwart him at a recent critical juncture.

But, despite the Duke’s continuing bad press, the Howard Vyse family had enjoyed the Cumberland patronage too long to want to risk being seen to upset it. Perhaps that was the reason why, despite the death of George IV some three years before, and Knighton’s consequent loss of influence, the Colonel forbade not only the marriage itself, but also (at least to begin with) any contact between the two families. xxvi Although, after a while, he seems to have thought better of this particular draconian measure, xxvii Vyse went on forbidding his eldest son’s marriage for the next six years.

The real problem, as George finally explained to Richard Seymour in February 1838, was that he was entirely financially dependent on his father. If George defied the Colonel, he – and his future bride – would be deprived of a significant source of income; George’s army pay would of course have been negligible.

But the time was to come when, income or no income, George had had enough, and, on 29th August 1839 – for better or for worse, and whether the combined noses of his father and the Duke of Cumberland were put out of joint or not – he and Lizzy were married at her home parish in Devon.

There are no reports of how the Duke took this news. Did Vyse really think that Cumberland would hold a grudge for so long? Sir William Knighton had been dead for three years, and, by 1839, the Duke might have had other things to worry about: following the death of William IV in 1837, he was now King of Hanover, and had his work cut out dealing with problems associated with the Hanoverian constitution. The Colonel’s name is mentioned infrequently, if at all, in conjunction with that of the Duke; did Vyse perhaps overestimate his own importance in Cumberland’s eyes? True, he was one of the Duke’s equerries: but, until 1837, there were six or seven other equerries. xxviii All in all, it is uncertain to what extent Vyse felt he might have to mend any bridges

However, in 1840, the year after George and Lizzy’s wedding, the first two volumes of Vyse’s magnum opus, Operations carried on at the Pyramids of Gizeh in 1837, were published, arousing much interest in certain scholarly circles. Although there is no evidence of the King of Hanover ever reading it, the work carried a dedication to Princess Augusta Sophia, his sister.

The third volume, by Vyse and civil engineer John Shae Perring, Appendix to Operations carried on at the pyramids of Gizeh in 1837, appeared in 1842. Right at the end of that volume appears a slightly incongruous section by Vyse entitled “Horses in Egypt and Syria,” which contains the following paragraph:

In the autumn of 1836 [sic] 1 saw at Kalisch in Poland a corps of cavalry from Karabah (near Teflis); their horses were low, but very strong, and appeared to be well-bred … remarkably fresh after a long and difficult march from their own country. xxix

With due allowance for the mistaken date (which should have read 1835), xxx the reader can see that this was some three months before Vyse’s arrival in Alexandria and later travels in the Near East..

But why – if Vyse had supposedly left England for Egypt – had he gone to Poland?

i Gentleman’s Magazine 1825 (pt II): 180.

ii E.g., D-HV/B/32/18 16th May, 1800 R. Vyse to Duke of Cumberland; D-HV/B/32/31 11th March, 1802 Duke of Cumberland to R. Vyse; D-HV/B/32/34 2nd April, Duke of Cumberland to R. Vyse.

iii D-HV/B/32/13 28th January, 1800 R. Vyse to Duke of Cumberland;D-HV/B/32/14 2nd February, 1800; Duke of Cumberland to R. Vyse; D-HV/B/32/18 16th May, 1800 R. Vyse to Duke of Cumberland; D-HV/B/32/21 10th June, 1801 Duke of Cumberland to R. Vyse; D-HV/B/32/39 2nd July, 1802 R. Vyse to Duke of Cumberland; D-HV/B/32/44 27th January, 1803 Duke of Cumberland to R. Vyse. Gentleman’s Magazine 1853; August: 200.

ivFuneral of Her Royal Highness The Princess Augusta Sophia. Date: Saturday, Oct. 3, 1840 The Times (London, England) Issue: 17479.

v Court Of King’s Bench, Tuesday, June 25, Wednesday, June 26, 1833 The London Times Issue 15201, p. 6. For a detailed account, see Bird, A. (1966), The Damnable Duke of Cumberland: 88-97.

vi In previous years, he had claimed to have grievances for the way in which Cumberland treated him (“Particulars Respecting Sellis”. Thursday, July 5, 1810 The London Times Issue: 8025). But Bird argues that he was treated well (88).

vii London Gazette, 16722: 791 (21st April 1813). He was still in the post in 1835 (The Royal Kalendar 1835: 129.)

viii Bird: 125.

ixBird: 9.

x Bird: 193.

xi Bird: 196. “ … notwithstanding his staunch Toryism and impassioned opposition to Catholic Emancipation … [Oxford] refused a degree … “ (Reminiscences of Many Years, Teignmouth, 1878, vol. II: 143).

xii Bird: 196. Thomas “Tommy” Garth was born in 1800, most likely the son of Lt. Col. Thomas Garth (1744-1829), widely believed to have been the lover of Princess Sophia.

xiii He was upset at her death in 1848 (Bird: 313).

xiv Bird: 200.

xvVan der Kiste, J. (2004), George III’s Children: 172.

xvi See also here.

xviiGeorge IV and Sir William Knighton, A. Aspinall, The English Historical Review. Vol. 55, No. 217 (Jan., 1940), pp. 57-82: 79. Bird: 211.

xviiiAspinall 1940: 79-80; 79, n. 6: Cumberland to Eldon, 30th March 1830. In an earlier letter to Lord Eldon (31st January1830), Cumberland, although not naming him, refers to Knighton disdainfully as “a medical gentleman.”

xix Bird: 205-6.

xxVan der Kiste, J. (2004), George III’s Children: 173-4.

xxi The Letters of King George IV, 1812-1830 … ; v. III February 1823-June 1831 / edited by A. Aspinall ; with an introduction by C.K. Webster. 1938; 470-1 [Knighton’s Diary, 1577] 9 Feb 1830.

xxiiAspinall:1938; 472 [Knighton’s Diary, 1578] 20 Feb 1830. But Cumberland was soon back at his brother’s side (Bird 210).

xxiiiCharlotte Frost (2011), Sir William Knighton: The Strange Career of a Regency Physician: 108.

xxiv Bird: 213.

xxv See here (543), and also here (9).

xxviSeymour: 21st February 1833.

xxviiOn 4th November 1833, Vyse wrote to Richard Seymour offering him some temporary livings (which Seymour refused), possibly in Suffolk (the diary is not very legible here); one of the livings appears to have been Friston, where Vyse had some property interests.

xxviii – https://courtofficers.ctsdh.luc.edu/lists/List%2038%20Household%20of%20Prince%20Ernest%20List.pdf, p. 5.

xxix144, n.

xxx The correct date is shown in a copy of the article that appeared in The Sporting Review, ed. by ‘Craven’. Vol IV, July 1840, 413, n.