Michael E. Moseley

Department of Anthropology

University of Florida

Gainesville Florida

32611-7305

moseley@anthro.ufl.edu

Submitted August 10, 2004 for Perú y el Mar: 12000 Años del Historia del Pescaría.

Pedro Trillo, Editor. Sociedad Nacional de Pesquería. Lima, Peru, 2005

Reproduced with permission by Michael Moseley

Caral Civilization Peru Weblog: The Origins of Civilization in Peru

ZONA ARQUEOLÓGICA CARAL UNIDAD EJECUTORA 003 MINISTERIO DE CULTURA

The “Maritime Foundations of Andean Civilization” or MFAC hypothesis proposed that thousands of years ago the rich Andean fishery sustained the growth of early littoral populations, the rise of large sedentary communities, and the formation of complex societies and the established the foundations of coastal civilization. The basic tenants of this scenario were initially formulated in the 1960’s and early 70’s by a small number of American, Andean and Russian scholars working independently of one another.1 When I popularized the hypothesis in 1975 there was evidence that platform mounds or huacas had been built at some early settlements on the coast of Peru. I drew heavily upon Aspero, a 15 ha settlement with six mounds located on the north side of the Supe Valley. However, there was little available evidence of elites or an upper class at Aspero or elsewhere. Therefore, MFAC proposed that early fishing societies developed the organizational foundations for coastal civilization, but civilization itself arose after 1800 BC with the introduction of pottery, the intensive cultivation of staples and the construction of large-scale irrigation systems.2 The proposition that fishing societies could evolve to the very threshold of civilization was radical, unwelcome and critiqued as an economic impossibility.

I am pleased to report that new research demonstrates the original hypothesis understated the evolutionary achievements of early Andean coastal societies. Following introductory observations about coastal fishing, evolutionary biases, and ancient diet, this essay first summarizes early littoral developments in Chile. It then turns to Peru and discusses the relationships of early fishing and farming. Next, investigations in the Supe Valley are discussed and the essay concludes with the revolutionary research by Dra. Ruth Shady who convincingly argues for the rise of civilization in preceramic times.3

During the 1990’s net harvesting of small schooling fish made Peru and Chile the world’s third and forth leading fishing nations. Anchoveta and small fish were similarly the staples of preceramic littoral societies, although a wide range of other marine fauna were consumed. Whereas most all of the Andean near-shore waters can be fished, less than 10% of the adjacent desert was traditionally farmed from short, steep streams and rivers feeding irrigated valleys.

Farming and fishing are generally separate and distinct professions because higher returns can be secured by pursuing one or the other rather than both together. Fishing is governed by lunar and tide cycles that are not congruous with farm work that is scheduled by solar and rainfall cycles. Economic organization is also different. Due to irregular topography, long canal systems maintained by large corporate work forces farm the majority of reclaimed land. Alternatively, small craft manned by small crews can efficiently net harvest the entire coastline throughout most of the year.

At the time of Spanish conquest indigenous fishing and farming were also separate professions along most of the coast. Self-segregated populations that lived apart pursued them. People married within their respective vocations and sometimes the professions spoke different dialects. Maritime specialists used shoreline gardens to cultivate tatora reeds for watercraft. However, they did not grow staples nor pay taxes or tribute with agricultural produce as farmers did. Nonetheless, there was an essential symbiotic relationship between the two professions with barter facilitating the exchange of marine protein for cultivated carbohydrates. Presumably, similar relationships prevailed earlier in time. But, before the advent of farming, fishing was the principal way to make a living along the arid coast for many millenniums. People were extracting seafood at the southern Peruvian sites of Quebrada Jaguay and Quebrada Tacahuay some 12,000 years ago. 4 These ancient beginnings make fishing the oldest enduring occupation in Peru and a profession of continuing national importance.

When the Spanish reached the Andes prosperous seaboard communities were symbiotically aligned with agrarian populations. In other regions fishing thrived where farming was absent. In North America European explorers encountered maritime mound-building societies along the Florida Gulf coast and sophisticated littoral chiefdoms in the north Pacific. Thus, there is long standing ethnohistorical documentation of high levels of development among indigenous people who exploited prolific fisheries.

Unfortunately, people who make a living from the sea were viewed as unruly, if not uncultured by the 19th century European Intelligentsia. Victorian savants were particularly upset by reports portraying the seeming ease with which native people secured seafood. For example, written about 1573, an anonymous account of the large Chincha maritime populace says:

… y parecia la población de esta gente una hermosa y larga calle llena de hombres y mugeres, muchachos y niñas, todos contentos y gozosos por que no entrando en la mar, todo su cuidado era beber y baylar, y lo demás.

( … and the settlement where these people lived seemed to consist of a wide and beautiful street full of men and women, boys and girls, who, when not going to the sea to fish, were all happy and pleased and whose only concerns were drinking and dancing and suchlike) 5

Accounts of people making a reasonable living without great effort was an affront to the Protestant work ethic of the bourgeoisie. To subsist well and toil arduously in cultivated fields or in capitalist factories was an anathema to the intellects that formulated the foundations of contemporary evolutionary discourse.

To knock a limpet from the rocks does not require even cunning, that lowest power of the mind

pronounced Charles Darwin of Tierra del Fieguo’s Yahgan fisher folk.6 Equating seafood acquisition with impaired mind power, and by inference-impaired potentials for cultural development-formed a stigmata that was then cemented into the foundations of social evolutionary theory.

Anything less than grueling labor in tilled plots or industrial plants was an abomination to Lewis Henry Morgan’s 1877 theory of cultural development espoused in Ancient Society. 7 Subtitled “Researches in the Lines of Human Progress From Savagery Through Barbarism to Civilization,” the treatise set forth the enduring axiom that agriculture was the singular evolutionary pathway to cultural complexity and civilization. Notably, it also characterized North Pacific littoral populations as the most primitive of all ethnographic societies surviving on earth. Consequently, these complex seaboard chiefdoms were ranked as archaic savages developmentally below the simplest of migratory hunter-gatherer bands and only marginally above the fossil primate ancestors of humans. Morgan’s formulations influenced Engel’s socialist evolutionary theory. Therefore, people of different political persuasions came to believe that an uninformed dietary choice at the food market for social progress condemned fishing societies to evolutionary dead ends! Unfortunately, this enduring theoretical myth is completely divorced form the economic reality that fishing can be a very prosperous profession.

Civilization requires calories to support activities that are not directly related to food production. Ancient dietary remains in the form of garbage and coprolites are generally well preserved at coastal desert sites. Determining what people ate requires very careful archaeological recovery with fine-mesh and microscopic analysis because many remains are tiny, including those of little fish and seeds. Virtually all preceramic sites where detailed dietary studies have been conducted indicate that people obtained their protein from the sea with anchoveta and sardena generally being the maritime staple. Yet, people also consumed plant foods. Seeds as well as small fish can be completely consumed. They can also be dried, ground into meal and consumed as flour or meal. Therefore, it can be difficult to discern if people of the coastal desert obtained the majority of their calories from marine or terrestrial resources.

The chemical and stable isotope composition of human bone is a critical gage of the relative amounts of marine and terrestrial foods that ancient individuals consume over a lifetime. Analysis of strontium and stable isotope ratios in human remains from the Peruvian preceramic settlement of La Paloma document a very high consumption of marine food indicating that most of their calories came from the sea.8 The site dates between about 6000 and 4000 BC and abundant anchoveta and small fish remains were the dominant intestinal remains recovered from 90 well preserved Paloma corpses. They were also the dominant constituents of coprolites as well as food trash.

In northern Chile strontium analysis and stable isotope ratio determinations have been preformed on 62 preceramic Chinchorro adults, dated between 4000 and 2000 B.C. Analysis implicated an average consumption of 89% marine foods, complimented by 6% terrestrials plants, and 5% land animals. Nearly identical dietary values are reported for an earlier corpse dated to 7020 +/- 255 B.C.9 Unfortunately, without additional isotopic analysis on other early coastal populations it cannot be said, with confidence, that all preceramic littoral populations drew the majority of their calories from the sea. Nonetheless, it can be said that most drew more than 90% of their protein from the sea.

MARITIME SOCIAL COMPLEXITY IN CHILE

A Chilean version of the maritime hypothesis has long been championed by archaeologist Agustín Llagostera. 10 Here the earliest artificial mummification in the world was practiced by so called Chinchorro populations between about 5,000 and 2,000 BC. These fisher folk resided along the coast from Antofagasta north through Arica and into the Ilo region of southern Peru. The vast majority of Chinchorro people were interred in a natural state without body modification Although artificial mummification was practiced for three millennia, it was very rare. The known sample of modified corpses numbers about 200 and all came from cemeteries with simple inhumations.11

Artificial mummification procedures were highly variable. They ranged from resinous encasement of fetuses through minimally invasive organ removal to complete cadaver disassembly. The latter included the stripping and disposal of organs and muscle, the grinding of long bone articulation surfaces to facilitate re-joining, and the reassembly of the skeleton with wooden shafts supporting the cranium, trunk, arms and legs. Reeds replaced extremity muscles and supported the repositioned tanned skin. The eyes, nose and mouth were sculpted on a clay facial overlays, the body surfaces were then painted and a cranial cap of human hair was added to the head.

The end products were statue-like objects. In certain cases the mummies were keep accessible and ritually manipulated resulting in damage what was carefully repaired. Mummies were buried in cemeteries with natural interments and in some cases conserved juveniles were jointly interred with an un-mummified adult, presumably a parent. However, joint interments of mummies, such as children and adults, also occurred. One assemblage, apparently a family, was multigenerational with children, two adults of reproductive age, and a very elderly individual. 12

Significantly, most mummified corpses are those of neonates and juveniles leaving adults in the minority. The preponderance of immature individuals implies that entitlement to privileged mortuary treatment was social prerogative inherited at birth. It was certainly not an honor that babies and children achieved by a lifetime of good works. Inheritance of privilege is a hallmark of nascent social complexity. It is an initial step toward civilization. However, even after the later introduction of irrigation agriculture coastal societies of southern most Peru and northern Chile did not erect platform mounds or large architectural monuments. In part, this is because the valleys of the region are quite small and in comparison to those of central and northern Peru that offer much greater agrarian potentials. Although southern developments were simpler they were firmly rooted in early maritime adaptations. Chinchorro mummies testify to the inheritance of privileged status and early social differentiation. Thus, Andean fishermen can take pride in the fact that their profession lead the world in artificial mummification long before ancient Egyptians began the practice.

PERUVIAN MARITIME ADAPTIONS

Historically the anchoveta fishery has produced its highest yields in waters along central and northern Peru. It is not surprising that this region witnessed precocious evolutionary developments between about 3000 and 1800 BC. Large architectural works were erected at a number of preceramic settlements. MFAC originally proposed that these works were products of hierarchical corporate organization with a minority of individuals directing activities of the majority. Ruth Shady’s 13 innovative investigations indicates that a class of leaders residing in elite architecture headed the chain of command in the Rio Supe area. Here hierarchial organization was associated with the rise of cities and urbanism, with the integration of adjacent valleys and state formation, as well as with the crystallization of preceramic civilization. Transpiring about one millennium earlier than expected, these developments make the Supe region the oldest cradle of civilization in the Americas. This achievement had unusual economic foundations involving both fishing and farming.

Use of domesticated plants has substantial antiquity in South America and the maritime hypothesis attempts to model the relationships of early fishing and farming. Although the near-shore Peruvian fishery could feed multitudes, making a living from the sea depended upon terrestrial resources including fresh water and wild vegetation that are not abundant. Plants supplied fiber for fishing line and nets as well as for clothing. They also provided floats for nets and material for watercraft, housing and fire fuel. Exploitation of finite desert resources increased over time as the size of maritime populations grew. To feed more people early Peruvian societies intensified the harvesting of anchoveta and small schooling fish. This required amplified production of line, net and watercraft that eventually overrode the limited supplies of natural desert vegetation. To sustain seaboard adaptations and population growth littoral people had to develop alternative resource supplies. The viable alternative, plant cultivation, was well established in Ecuador and the tropics well before 4000 BC. Here cultigens were agricultural staples used to feed people. Significantly, when Peruvian maritime populations began to engage in plant husbandry they emphasized cultigens, such as cotton and gourd, that sustained fishing and focused secondarily upon crops that feed people. This is a unique situation in the annals of the world’s early civilization. Yet, it is intelligible if coastal farming was initiated by fishing people for the purpose of producing “industrial cultigens” yielding fiber, net floats, containers, and wood essential to maritime adaptations.

Assemblages of botanical remains from coastal preceramic settlements generally include large quantities of junco and tatora reeds needed for making mats, esteras, as well as watercraft and it is likely that these un-domesticated plants were cultivated in brackish water ponds and lagoons. After about 3,000 BC perennial cotton (which has wild ancestors in northern Peru) became one of the most ubiquitous cultigen at desert sites. Well preserved cotton fiber, seeds, bowls parts are typically very abundant. Tree fruit, such as of guayabana, guava, pacae, lucuma and avocado, is also surprisingly common but they vary by type from site to site. The trees were no doubt very important sources of wood as well as fruit. Gourd is a common industrial cultigen that provided net floats and containers in pre-pottery times. Squash, several types of beans, palillo and chili peppers are generally present. They are generally less common than industrial cultigens and fruit, but more frequent than staples.

Staples are domesticated plants that yield abundant harvests, which can be stored and consumed until the next harvest. Potential preceramic staples include: achira, camote, jicama, maize, potatoes and yucca. Their presence is very erratic. Some sites have none, others may have three or four types, but each is generally represented by only a few specimens. There is generally good preservation of plant remains at both coastal preceramic and early ceramic age sites. Therefore if agricultural staples were of early dietary significance, then their remains should be just as prevalent as those of a yucca, potatoes, maize and other food plants are at early ceramic agricultural sites. However, this is not the case.

Preceramic fields and agricultural works do not survive, but reeds were likely grown in lagoons and in brackish water totoral pits excavated behind beaches such as those used by the fishermen of Chincha. Domesticated plants require sweet water that was often inconveniently located inland and away from the littoral focus of maritime activity. Most agricultural staples require constant care from soil tilling and sowing through harvesting and processing. Significantly, the most common and abundant cultigens present at coastal preceramic sites are ones that did not require constant care. Fruit trees and cotton shrubs were perennials that grew for years. Annuals such as squash and beans were hearty and could be sown, left and later harvested. This allowed fishermen to farm on an intermittent basis.

Early cultivation presumably transpired in lands that were self-watering or easily watered. The flood plains of coastal rivers are self-watered by springtime “avenida” floods and simple canals could be used to irrigate river bottom areas. Terrain easily irrigated from springs and pukios also occurred where there were high phreatic levels, such as near valley mouths. Yet, in the absence of large scale canal irrigations, terrain suitable for simple horticulture was limited.

Andean coastal rivers have generally down-cut their channels and lie within deeply incised banks. Consequently, easily watered land accounts for less than two percent of the arable coastal terrain in production today.

Control of scarce commodities contributes to the evolution of hierarchial organization and civilization. Preceramic marine resources were not in short supply nor was their explotitation readily regulated. Alternatively, arable land was a scarce commodity, and access to it could be controlled. As populations grew and seining of the sea intensified, rights to horticultural land presumably became ever more important and settlements that controlled access to fields were advantaged over ones that did not.

Farming was most easily conjoined with fishing at the mouths of those valleys that offered wide river flood plains, easily accessible ground water or both. This was the location of Aspero and other large monuments known at the time MFAC was initially formulated. However, the importance of arable land was overlooked. For example, 2 km in from the sea, the Rio Chillon has an anomalously wide section of river flood plain with some 130 ha of arable bottomland. This horticultural resource is now thought to account for the adjacent location, if not size, of El Paraiso a vast masonry complex sprawling over some 58 ha.14 With very late preceramic dates, this monumental complex is unusual because habitation refuse is scarce in and around the masonry ruins. Substantial garbage and midden deposits are typically associated with sites of this size range. If the situation at El Paraiso is not a product of aberrant preservation, then many of the people who helped built the complex did not reside there on a year-around basis. Being somewhat inland, it was not a particularly convent place for fishermen to live. Yet, they must have contributed to the construction and maintenance of this very large monument. Indeed, analysis of dietary remains indicates that most all protein came from the sea. If people who resided elsewhere along the littoral provided labor and provisions for El Paraiso, then their recompense presumably entailed access either to the adjacent farm land or to its products. It is not clear who did the farming at El Paraiso. Non-residents may well have contributed labor during times of sowing and harvesting. Of course, there would have been greater commodity control if the full time residents did all farming. These uncertainties aside, the ability to mobilize labor resources from different communities and focus them on centralized undertakings are trademarks of hierarchial organization and early civilization.

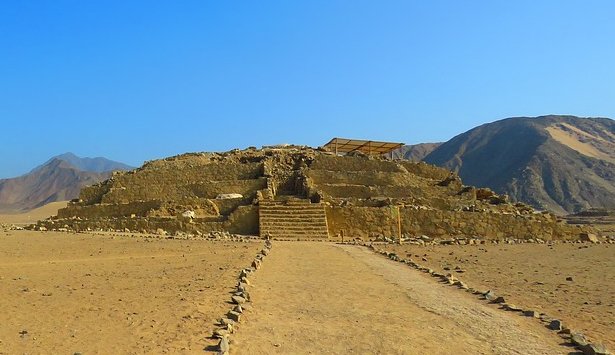

EARLY CIVILIZATION IN THE RIO SUPE

The Rio Supe is a small drainage but it has early sites that have long attracted scientific attention. These settlements and monuments are products of precocious development that has often exceeded theoretical expectations. For example Max Uhle discovered coastal Aspero almost a century ago. He described its 15 ha spread of carbon-rich garbage as resembling deposits from an “old foundry.” Yet, Uhle did not recognize that it was a large maritime community because he considered fishermen primitive and barbaric in accordance with evolutionary theory of the time.15 The site was investigated again in 1943, but there was still no understanding that early fishermen could live in sedentary communities or build earthworks. Therefore, it’s dating remained uncertain and half a dozen platform mounds were dismissed as natural hills. The situation changed as archaeologist began to identify and date preceramic sites elsewhere along the coast. Theoretical acceptance of maritime societies had improved when Aspero was again investigated in the early 1970’s.16 Excavations exposed late phase summit buildings on the top of two platform mounds. One, Huaca de los Idolos, produced a 3055 BC radiocarbon assay, and the other, Huaca de los Sacrificios dated about two centuries earlier. 17

At this time of these explorations a contemporary complex, Piedra Parada, was recognized on the south side of the valley. Early aerial photographs of the Supe drainage revealed a number of large inland sites with architectural features, such as circular sunken courts, that seemed to have considerable antiquity.18 In the 1980’s some of the up-valley sites were auger tested. Certain cores yielded diagnostic preceramic artifacts .19 Yet, the results received little attention because they did not conform to theoretical views of the time that large preceramic settlements were restricted to the coast.

Shady and her team subsequently identified and mapped 15 inland preceramic complexes reaching 40 km up the Supe drainage. The ruins support her contention that America’s oldest American civilization arose in Supe. This proposition is based upon new data and well reported research.20 Although the concept of preceramic civilization is revolutionary, it should come as no surprise. The early sites of Supe have a long history of exceeding evolutionary expectations.

It is significant that similar early developments have not been detected in well-studied valleys to the north beginning with the Rio Casma. Nor, are they evident from the Rio Chancay south. Thus, if all preceramic populations had equal developmental capabilities, then it must be suspect that the Rio Supe region offered unusual natural resources for furthering early social evolutionary potentials. The intensity of modern fishing activity in the region indicates that it is well graced with maritime potentials. However, the Supe Valley is small and out produced by larger adjacent valleys. Nonetheless, shallow river flood plains and high phreatic conditions favorable to simple canal irrigation seemingly conferred economic an unusual advantage for early cultural development.

Situated more than 20 km inland, Caral is the second largest preceramic settlement in the valley, surpassed only by 79 ha sprawl of Era de Pando. If not a preceramic capitol, then Caral is certainly a prehistoric city both in size and in differentiation of urban space. There are lower class barrios where people resided in humble housing of cane. There are also elite quarters of masonry and mortar construction with plastered and painted walls. Similar construction also characterized an artisan workshop where jewelry and stone artifacts were produced. Elite quarters are located around the civic core where some are immediately adjacent to particular mounds or physically annexed to them.

With a basal length of 153 m, and a width of 109 m, the largest monument, called the major pyramid, is fronted by a circular court and rises in terraced steps to a height of 28 m. The summit is occupied by courts and rooms often ornamented with wall niches and geometric friezes. This big building overlooks a large rectangular plaza that is framed by more than half a dozen other mounds and monumental works. All of the pyramidal mounds were built in stages interspersed with epochs of use. Most rise in steps or terraces and some are associated with circular fire alters on their summits or at lower levels. Yet, the configuration of each mound and its summit buildings is unique and design concepts seem much more variable than those of traditional Catholic churches.

Shady proposes that pyramidal mounds were temples and that Caral was a sacred center. She cogently argues that religion was the principal source of early social cohesion and the main means of managing the political economy. 21 Most scholars agree that governance transpired in the name of the gods in preceramic and early ceramic times. If the multiple pyramidal mounds at Caral, Aspero and other large complexes were temples then different facilities presumably served different deities. Differences in mound size suggest hierarchical differences in the preceramic pantheon. At Caral the major temple most probably served the major deity, while smaller mounds served subordinate divinities. It may be that subordinate temple divinities had to be placated before gaining access to higher ranked gods. It cannot be said that the major temple deity at Caral was the same god that the largest temples at other sites served. Nor, can it be said that different communities or cities had different patron gods without further exploration at other complexes. At sites such as Caral it is not clear if a separate local congregation sustained each separate temple or if the entire community supported all facilities equally. Thus, there are many issues for further research.

The proposition that early state formation transpired in the Rio Supe is based on calculations of the size and volume of platform mound and monumental construction at the 17 preceramic complexes in the drainage.20 The labor requirements to produce the total volume of preceramic construction are inferred to have exceeded what residents of the small valley could have provided. Therefore, labor if not other resources were presumably extracted form adjacent valleys to support the Supe complexes, particularly the larger ones.

State formation in the Supe region would have been a gradual but complex process. Integrating local populations of the valley should have preceded the extraction of resources from adjacent valleys. Local integration must have required time. There are no grounds to believe that all 17 preceramic sites in the drainage were founded at the same time. Radiocarbon assays of 3055 BC from the late phase summit architecture of Huaca de Los Idelos at Aspero is the oldest of all preceramic dates from the region. Because the Huaca was built in stages separated by epochs of temple use, the initial construction of the facility situated at much greater depths must have substantially greater antiquity.

If Aspero is the oldest of the Supe sites then it may be hypothesized that other complexes were founded sequentially later and progressively further inland as needs for farmland and its produce increased. The course of inland reclamation and settlement would not have been strictly linear because valley bottom water and arable land are not homogeneously distributed in the valley. Nonetheless, it is useful to model the process of interior valley colonization as a prelude to state formation. Modeling begins with the presumption that folk-level origination was based upon kinship and early descent systems may have been generally similar to those of later ayllu communities. If the populations of older settlements, such as Aspero, gave rise to younger daughter colonies that moved inland, settled and later produced own offspring satellites communities, then acknowledged common ancestry might assist political and religious integration.

Warfare is a recurrent theme in many theories of state formation. One holds that arable desert land was a circumscribed resource. Competition for it grew as early populations grew in size. Upon reaching the limits of the resource the social order changed. Aggression became common because land could only be secured by taking it from others. Pervasive hostility generated new forms of hierarchial leadership to deal with new problems. These included the resolution of internal rivalries, the protection of local resources and the capture of external assets. Conquest and incorporation of external lands then lead to state formation. 22 The central tenant of this scenario is attractive because arable land was certainly a circumscribed resource. Yet, the Supe sites are not fortified and there is little evidence of preceramic armed conflict. This need not be surprising. If religion was the principal source of early cohesion and political integration, then the formation of a theocratic state may have relied more upon on evangelical conversion than upon physical coercion.

Ultimately, the hypothesis that Andean civilization had maritime foundations is easiest to confirm in Chile for three reasons. First, the earliest artificial mummies in the world are Chilean and include large numbers of children who inherited elite standing and privileged mortuary treatment that are indicative of early class formation. Second, there is little evidence that these people engaged in farming. And, third chemical analysis of bone from numerous humans indicates that people obtained 89% of their diet from the sea.

Fishing contributed to very complex development in Peru. Yet, it is not entirely clear how the maritime hypothesis articulates with these developments for two reasons. The first is that people were farming. And, the second is that there has been no dietary analysis of human bone chemistry for populations dating after 4000 BC. Lacking such analysis the relative contributions of fishing and of farming to general nutrition and to the caloric foundations of coastal civilization are speculative.

Remains of seafood and cultivated food occur at most preceramic sites but comparative analysis does not securely illuminate their relative dietary contributions. Therefore, speculation about nutrition is influenced by site location. At coastal sites, such as Aspero, people are presumed to have relied principally upon fishing. At inland sites, such as Caral, farming is presumed to have fed people. Drawing upon the Caral research, Haas and Creamer have asserted that rise of early civilization in the Supe valley was based upon agriculture and therefore does not differ form the origins of early civilizations elsewhere in the world. 23 Domesticated staples and domesticated animals were critical to other civilizations. In coastal Peru the situation is significantly different because agricultural staples were uncommon and protein came from the sea.

The difference is very evident in the food remains reported from Caral. 24 Guayaba (3025 specimens) is the dominant cultigen.

Cotton (2141 specimens), pacae (1563 specimens), zapallo (103 specimens) and frijol (19 specimens) are next in frequency. Potential staples include two specimens of maize, one each of camote and achira. If this botanical assemblage is representative of the relative abundance of the plants that were farmed, then it is difficult to understand how horticulture alone could sustain a large population. Expectably seafood remains are well represented. Marine birds, including guanay and coromoran, were consumed. For the most the most common mollusks the minimum number of individuals were 1326 for choros and 879 for machas. For the most the most common the minimum number of individuals were 449 for anchoveta and 148 for sardine.

To assess food requirements it is useful to divide the residents of Caral into three possible groups with varying subsistence needs. One would be transients, such as religious pilgrims or state workers mobilized from other areas. Another group of inhabitants could be people who lived at Caral regularly each year but only seasonally. The third and most important group would be permanent, year-around residents including priests, functionaries, elites and full-time farmers. This segment of the population would place the greatest demands upon the local subsistence economy. Unfortunately, transient, seasonal, and permanent residency are extremely difficult conditions to distinguish archaeologically at any site. Nonetheless, they are features of state level organization that require serious, albeit tentative, consideration in preceramic contexts.

External provisions, particularly seafood, may have been supplied to Caral by three possible means that were not mutually exclusive. The first would be tribute brought in by transients. The second would be part-time annual residents who brought in their own provisions if not also tribute. In theory, these would be working class people who maintained a permanent urban household. They lived at Caral during the agricultural season or when religious occasions required, but then dispersed to the coast to reside where they could fish. The scarce remains of staples raise the serious possibility that not everyone at Caral could live there year around. Staple domesticates are important because they can be harvested in abundance and then stored to feed people until the next harvest. This is not possible with guayaba, pacae, zapallo, and frijol. Fishing tackle has not been found at Caral. Yet, if people maintained coastal as well as interior households then hauling nets and gear 20 kilometers inland would not be practical.

Finally, seafood was most certainly obtained by means of exchanging cotton and cultivated produce for marine products as Shady emphasizes.13 If preceramic fishing and farming were separate full-time professions then they must have been symbiotically linked through economic exchange as in later times. Yet, I would speculate that farming which emphasized industrial cultigens rather than staples was highly dependent upon maritime adaptations and that fishermen essentially fed coastal farmers. This can be framed as a hypothesis: the residents of Caral obtained more than 50% of their nutrition from the sea. The proposition is readily testable by dietary analysis of human bone chemistry.

In overview, human exploitation of the sea was underway 12,000 years ago in Peru and fishing is the oldest ongoing occupation pursued by Andean people. The profession is exceptionally productive because the near-shore waters are unusually rich. The bounty of the sea sustained precocious cultural developments. About 7000 BC Chilean fishing societies began artificially mummifying important people and their children. Predating Egypt by millennia these are the oldest mummies in the world.

By 5,000 years ago sedentary maritime communities were building temple mounds in Peru. Within one millennium civilization had crystallized in Rio Supe region, as revealed by new research. Although people also farmed, the focus was upon industrial cultigens that could support fishing, such as cotton for nets and gourds for floats. If chemical analysis of human bone demonstrates that people received most of their calories form the sea, as is expected, then Peruvian fishermen can be credited for creating the earliest civilization in the Americas. This is a truly unique achievement in the annals of human evolution!

Notes

1 The origins and development of the maritime hypothesis are summarized in: Moseley, Michael E. Maritime Foundations and Multilinear Evolution: Retrospect and Prospect. Andean Past #3. Ithaca, New York. 1992, pp. 8-11.

Examples of early contributions include:

Engel, Frederic. A Preceramic Settlement on the Central Coast of Peru: Asia, Unit I. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 51 (3), Philadelphia, 1963.

Fung P. Rosa. El Temprano Surgimiento en el Perú de los Sistemas Socio-Políticos Complejos: Planteamiento de una Hipótesis de Desarrollo Original. Apuntes Arqueológicos 2. Lima, 1972, pp. 10-32.

2 Moseley, Michael E. The Maritime Foundations of Andean Civilization. Cummings Publishing Company. Menlo Park, California, 1975.

6 Darwin, Charles. Journal of Researches into the Natural History and Geology of the Countries Visited during the Voyage of HMS Beagle round the World. J.M. Dent, London. E. P. Dutton. 1906 [1845], p. 206.

7 Morgan, Lewis Henry. Ancient Society, or Researches in the Lines of Human Progress from Savagery through Barbarism to Civilization. Henry Holt. New York, 1877.

8 Benfer, Robert A. The Preceramic Period Site of La Paloma, Peru: Bioindications of Improving Adaptation to Sedentism. Latin American Antiquity 1. Washington D.C., 1990, pp.284-318.

9 Arriaza, Bernardo. Beyond Death: the Chinchorro mummies of ancient Chile. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington D. C., 1995.

10 Llagostera, Agustin. Tres dimensiones en la conquista prehistórica del mar. Un aporte para el estudio de las formaciones pescadores de la costa sur andina. In, Actas del VIII Congreso de Arqueología Chilena: (Valdivia, 10 al 13 de octubre de 1979) / Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología, Universidad Austral de Chile. Ediciones Kultrún, Santiago, 1979, pp. 217-245.

Llagostera, Agustin. Early Occupations and the Emergence of Fishermen on the Pacific Coast of South America. Andean Past #3. Ithaca, New York. 1992, pp. 87-109.

11 Allison, Marvin J., Focacci, Guillermo, Arriaza, Bernardo, Standen, Vivian, Rivera, Mario y Lowenstein, Jerold. Chinchorro, momias de preparación complicada: Métodos de momificación. Chungara: Revista de Antropología Chilena No. 13 (Noviembre 1984), pp. 155-173.

Arriaza, Bernardo. Beyond Death: the Chinchorro mummies of ancient Chile. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington D. C., 1995.

Rivera, Mario A. The Preceramic Chinchorro Mummy Complex of Northern Chile: Context, Style, and Purpose. In Tombs for the Living: Andean Mortuary Practices, Tom D. Dillehay editor. Dumbarton Oaks, Washington D. C.,1995, pp. 43-78.

13 Shady, Ruth. Caral Supe: la civilización mas antigua de América. Proyecto Especial Zona Arqueológica Caral – Supe/INC. Lima, 2003.

14 Quilter, Jeffrey. Architecture and Chronology at El Paraíso, Peru. Journal of Field Archaeology 12. Boston, 1985, pp.279-297.

Quilter, Jeffrey, Bernardino Ojeda E., Deborah M. Pearsall, Daniel H. Sandweiss, John G. Jones, and Elizabeth S. Wing. Subsistence Economy of El Paraíso, an Early Peruvian Site in Peru. Science 251. Washington D.C., 1991, pp. 277-283.

15 Rowe, John. Max Uhle, 1856-1944. A Memoir of the Father of Peruvian Archaeology. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 46 (1). Berkeley, 1954.

16 Moseley, Michael E. y Willey, Gordon R. Aspero, Peru: a Reexamination of the Site and its Implications. American Antiquity 38. Washington D.C., pp. 452-468.

17 Feldman, Robert. Aspero, Peru: Architecture, Subsistence Economy and other Artifacts of a Preceramic Maritime Chiefdom. Tesis Doctorado. Harvard University, Cambridge, 1980.

18 Kosok, Paul. Life, Land and Water in Ancient Peru. Long Island University Press, Long Island, 1965.

19 Zechenter, Elzbieta. Subsistence strategies in the Supe Valley of the Peruvian Central Coast during the Complex Preceramic and Initial Periods. Tesis Doctorado. University of California, Los Angeles, 1988.

20 Shady, Ruth; Leyva, Carlos; eds. La ciudad sagrada de Caral-Supe. Los orígenes de la civilización andina y la formación del Estado prístino en el antiguo Perú. Proyecto Especial Arqueológico Caral-Supe, Lima, 342 pp. Lima, 2003.

21 Shady, Ruth. La Religión como una forma de Cohesión Social y Manejo Político en los Albores de la Civilización en el Perú. Boletin del Museo de Arqueologia y Antropologia, UNMSM, año 2, (9), Lima, 1999, pp. 13-15.

22 Carnerio, Robert L. A Theory of the Origin of the State. Science 169. Washington D.C. 1970, pp. 733-738.

| References Allison, Marvin J., Focacci, Guillermo, Arriaza, Bernardo, Standen, Vivian, Rivera, Mario y Lowenstein, Jerold. Chinchorro, momias de preparación complicada: Métodos de momificación. Chungara: Revista de Antropología Chilena No. 13 (Noviembre 1984), pp. 155-173. Arica, 1984, 155-173. Alva, Walter. Las Salinas de Chao: Un Asentamiento Temprano, Observaciones y Problemática. Yunga 1 (1) Trujillo, 1987, pp. 33-70. Arriaza, Bernardo. Beyond Death: the Chinchorro mummies of ancient Chile. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington D. C., 1995. Benfer, Robert A. The Preceramic Period Site of La Paloma, Peru: Bioindications of Improving Adaptation to Sedentism. Latin American Antiquity 1. Washington D.C., 1990, pp.284-318. Bonavia, Duccio. Los Gavilanes. Mar, desierto y oasis en la historia del hombre. COFIDE-IAA. Lima, 1982. Carnerio, Robert L. A Theory of the Origin of the State. Science 169. Washington D.C. 1970, pp. 733-738. Darwin, Charles. Journal of Researches into the Natural History and Geology of the Countries Visited during the Voyage of HMS ‘Beagle’ round the World. J.M. Dent, London. E. P. Dutton. 1906 [1845]. deFrance, Susan D., Keefer, David K., Richardson, James B. y Umire Alvarez, Adan. Late Paleo-Indian Coastal Foragers: Specialized Extractive Behavior at Quebrada Tacahuay, Peru. Latin American Antiquity 12 (4). Washington D.C., 2001, pp. 413-426. Engel, Frederic. A Preceramic Settlement on the Central Coast of Peru: Asia, Unit I. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 51 (3), Philadelphia, 1963. Feldman, Robert. Aspero, Peru: Architecture, Subsistence Economy and other Artifacts of a Preceramic Maritime Chiefdom. Tesis Doctorada. Harvard University, Cambridge, 1980. Fung P. Rosa. El Temprano Surgimiento en el Perú de los Sistemas Socio-Políticos Complejos: Planteamiento de una Hipótesis de Desarrollo Original. Apuntes Arqueológicos 2. Lima, 1972, pp. 10-32. Haas, Jonathan y Creamer, Winifred. Response [to Amplifying Importance of New Research in Peru] Science 294 (5547). Washington D.C., 2001, pp. 1652-1653. Kosok, Paul. Life, Land and Water in Ancient Peru. Long Island University Press, Long Island, 1965. Llagostera, Agustin. Tres dimensiones en la conquista prehistórica del mar. Un aporte para el estudio de las formaciones pescadores de la costa sur andina. In, Actas del VIII Congreso de Arqueología Chilena: (Valdivia, 10 al 13 de octubre de 1979) / Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología, Universidad Austral de Chile. Ediciones Kultrún, Santiago, 1979, pp. 217-245. Llagostera, Agustin. Early Occupations and the Emergence of Fishermen on the Pacific Coast of South America. Andean Past #3. Ithaca, New York. 1992, pp. 87-109. Morgan, Lewis Henry. Ancient Society, or Researches in the Lines of Human Progress from Savagery through Barbarism to Civilization. Henry Holt. New York, 1877. Moseley, Michael E. The Maritime Foundations of Andean Civilization. Cummings Publishing Company. Menlo Park, California, 1975. Moseley, Michael E. Maritime Foundations and Multilinear Evolution: Retrospect and Prospect. Andean Past #3. Ithaca, New York. 1992, pp. 5-42. Moseley, Michael E. y Willey, Gordon R. Aspero, Peru: a Reexamination of the Site and its Implications. American Antiquity 38. Washington D.C., pp. 452-468. Quilter, Jeffrey. Architecture and Chronology at El Paraíso, Peru. Journal of Field Archaeology 12. Boston, 1985, pp.279-297. . Quilter, Jeffrey, Ojeda E., Bernardion, Pearsall, Deborah, Sandweiss, Daniel H., Jones, John G. y Wing, Elizabeth S. Subsistence Economy of El Paraiso, an Archaic Site in Peru. Science 251. Washington D.C., 1991, pp. 277-283. Rivera, Mario A. The Preceramic Chinchorro Mummy Complex of Northern Chile: Context, Style, and Purpose. In Tombs for the Living: Andean Mortuary Practices, Tom D. Dillehay editor. Dumbarton Oaks, Washington D. C.,1995, pp. 43-78. Rostworowski de Diez Canseco, Maria. Mercaderes del valle de Chincha en la época prehispánica: un documento y unos comentarios. Revista Española de Antropología Americana 5. 1970, pp. 170-171. Rowe, John. Max Uhle, 1856-1944 A Memoir of the Father of Peruvian Archaeology. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 46 (1). Berkeley, 1954. Sandweiss. Daniel H., McInnin, Heather, Burger, Richard L., Cano, Asuncion, Ojeda, Bernardino, Paredes, Rolando, Sandweiss, María del Carmen, y Glascock, Michael D. Quebrada Jaguay: Early South American Maritime Adaptations. Science 281. Washington D.C., 1998, pp. 1830-1832. Shady, Ruth. La ciudad sagrada de Caral – Supe en los albores de la civilización en el Perú. UNMSM, Lima, 1997. Shady, Ruth. La Religión como una forma de Cohesión Social y Manejo Político en los Albores de la Civilización en el Perú. Boletin del Museo de Arqueologia y Antropologia, UNMSM, año 2, (9), Lima, 1999, pp. 13-15. SHADY, Ruth 2000c Sustento socioeconómico del Estado prístino de Supe-Perú: Las evidencias de Caral-Supe. In Arqueología y Sociedad Nº 13: 49-66, MAA, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Lima. ISSN 0254-8062 Shady, Ruth. Caral-Supe, La Civilización más Antigua de América. Proyecto Especial Arqueológico Caral-Supe /INC. Lima, 2003. Shady, Ruth, C. Dolorier, F. Montesinos and L. Casas, 2000, Los orígenes de la civilización en el Perú: el area norcentral y el valle de Supe durante el arcaico tardío. Arqueología y Sociedad 13: 13–48. Museo de Arqueología y Antropología, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Lima. Shady, Ruth; Leyva, Carlos; eds. La ciudad sagrada de Caral-Supe. Los orígenes de la civilización andina y la formación del Estado prístino en el antiguo Perú. Proyecto Especial Arqueológico Caral-Supe, Lima, 342 pp. Lima, 2003. Standen, Vivien G. Temprana Complejidad Funeraria de la Cultural Chinchorro (Norte de Chile). Latin American Antiquity 8(2). Washington D.C., 1997, pp. 134-156 Zechenter, Elzbieta. Subsistence strategies in the Supe Valley of the Peruvian Central Coast during the Complex Preceramic and Initial Periods. Tesis Doctorado. University of California, Los Angeles, 1988. Dr Moseley’s “Maritime Foundations of Andean Civilization” (MFAC) has been one of the most influential hypotheses explaining the rise of Andean civilization. For the past ten years Dr. Ruth Shady has been researching Caral, which has highlighted a need to expand the MFAC to amplify the role that industrial agriculture played in the development of Andean civilization |