Researchers with a particular interest in the pre-Columbian Andes are fortunate that several highly valuable histories were written after the conquest by both Spanish and indigenous writers. In a rather ironic twist of fate, some priests such as Father Pablo Joseph de Arriaga actually recorded the customs of the Inca religion as they were attempting to destroy it and bring the Andeans to the Catholic faith.

Other chroniclers, Guaman Poma for example, wrote to persuade the Spanish King to let the Peruvian people rule themselves. The chronicler Garcilaso de la Vega, El Inca stands out among the chroniclers, both Spanish and Inca, for the depth and detail of his writings on the history and customs of the Andes.

Which came first, the chicken or the Spanish?

The debate concerning the presence of the chicken in the “New World” began early and is still ongoing. There is however no evidence, so far, that has withstood scientific scrutiny to support the idea that the chicken was present in the Americas before contact with the Spanish. Today, most of the writers who support an early chicken presence believe that the chicken was brought to American shores by the Polynesians. These writers also often seize on the words of Jose de Acosta who wrote in 1604:

But leaving these birds that govern themselves without the care of man, except onely for hawking, let vs now speake of tame fowle; I wondered at hennes, seeing there were some before the Spaniards came there, the which is well approved, for they have a proper name of the country, and they call a henne Hualpa, and the eggs Ronto, and they use the same proverb wee doe, to call a cowards a henne. (Acosta 1604 Ch. 35, p. 306)

When Acosta wrote these words, it had been 75 years since the Spanish made contact with the Inca Empire. Acosta himself only arrived in Peru in 1569, forty years after the conquest by the Spanish.

Garcilaso de la Vega is perhaps the best known of the indigenous chroniclers, the son of an Inca princess and a Spanish aristocratic Garcilaso spent the first twenty years of his life listening to his Inca mother and her relatives learning about his native land. He wrote about the chicken debate in some detail:

One writer [KR: Acosta] maintains that chickens existed in Peru before the conquest; and there are those who have striven to prove as much by advancing such proofs as the fact that the Indians have words for their language for the chicken, gualpa, and the egg, ronto, and their use of the same epithet as the Spaniards, in calling a man a chicken, meaning that he is a coward. We can settle these arguments by giving the facts of the case. Leaving the word gualpa till the last and taking the word ronto (which should be written runtu, the r being pronounced softly, for there is no double rr either at the beginning, or in the middle of words), this is a common noun meaning “egg” not the egg of the chicken in particular, but that of any bird whether wild or tame, and when the Indians wish to make it clear what bird the egg belongs to they name the bird and the egg as we do in Spanish, when we cay chicken’s or partridge’s or pigeon’s egg, etc. This is sufficient to dispose of the argument about the word runtu.

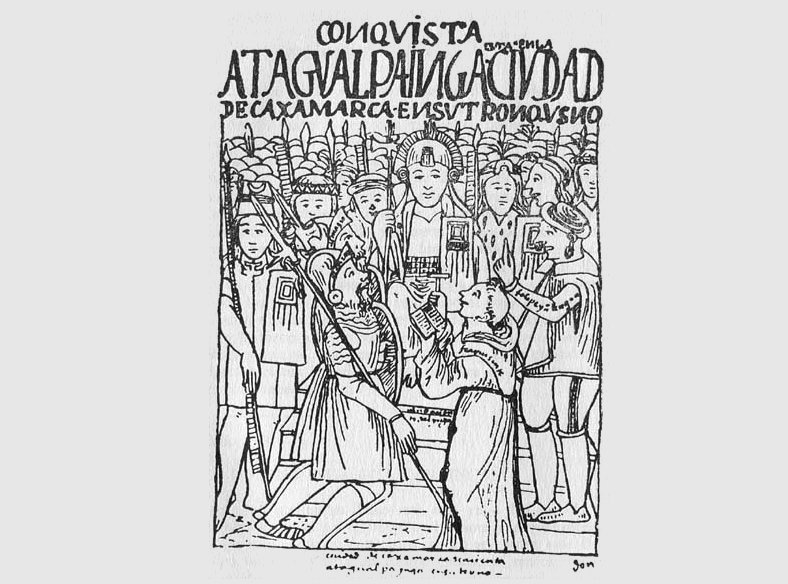

The epithet chicken applied to a coward has been taken by the Indians from the Spaniards in the ordinary course of daily contact and is an imitation of the their speech precisely in the same way as Spaniard who have been in Italy, France, Flanders, and Germany intermingle words and phrases they have picked up from foreigners in their Castilian speech after they have retuned to their own country. The Indians have done the same, though the Incas have an epithet for a coward which is even more appropriate: they say huarmi, “woman” using the word figuratively. The proper word for “coward” in their own language is campa and llanclla is “pusillanimous and weakhearted,”. So the epithet of chicken for a coward is appropriated from the Spanish and does not exist in the Indian language: I, as an Indian, can vouch for this. The name gualpa which the Indians are said to apply to chickens is written corruptly and shorn of two syllables; it should be atahuallpa, and is not a name for a chicken but for the last Inca of Peru, who, as we shall say in dealing with his life, displayed greater cruelty toward those of his own kith and kin than all the wild beasts and basilisk in the world. He was a bastard, but he cunningly and treacherously captured and killed his elder brother, the legitimate heir called Huascar Inca, and usurped the kingdom, destroying the whole of the blood royal, men, women, and children, with unheard of tortures and cruelest torments that can possibly be imagined, and not sated with the rage and savagery by slaughtering the closest servants of the royal houses, who, as we have said, were not private persons, but the whole villages, each of which performed a special task such as porters, sweepers, woodcutters water carriers, gardeners, cooks for the royal table, and so on. All these villages which were round Cuzco at a distance of four, five, six or seven leagues were destroyed, and not content with killing the inhabitants, he razed their buildings. These cruelties would have gone even further if the Spaniards had not cut them short by arriving in Peru when they were at their height.

As the Spaniards arrested the tyrant Atahuallpa on their arrival and soon put him to death by shamefully strangling him in the public square, the Indians said that their god, the Sun, had sent the Spaniards to take vengeance on the traitor and chastise and bring to book the tyrant who had slain their children and destroyed their blood. Because they had executed him the Indians obeyed the Spaniards as if they were envoys of their god, the Sun, deferring to them in everything and not resisting them in the conquest as they might have done, but rather worshiping them as children and descendants of their god Viracocha, the child of the Sun, who had appeared in dreams to one of their kings who was therefore call Inca Viracocha: the same name they therefore applied to the Spaniards.

This mistaken idea they had formed of the Spaniards became confused with an ever greater misconception: as the Spaniards introduced cocks and hens among the first thing brought from Spain to Peru, the Indians, when they heard the cocks crow, said that these birds were perpetuating the infamy of their tyrant and abominating his name by repeating “Atahuallpa” when they crowed, and they used to pronounce the word imitating the crowing of the cock. (Garcilaso de la Vega, 1609)

The writing of Garcilaso on this matter is substantiated by Santacruz Pachacuti, an obscure indigenous chronicler, who wrote:

In the end after Atahuallpa has been made prisoner and there the rooster crows, and Atahuallpa Ynga say, ˜Even the birds know my name, Atahuallpa.’ (Seligmann, 1987)

With the exception of Acosta, all the chroniclers both Spanish and Incan agree that the chicken was brought to the Americas by the Spanish, and that the name results from the Inca Atahuallpa, not the other way around.

Spaniards introduced cocks and hens among the first thing brought from Spain to Peru ~ Garcilaso de la Vega

Garcilaso states quite clearly that chickens were the first animal brought from Spain to Peru. To discuss this issue further we will turn to the scientific evidence.

In 2007, researchers announced that they had found pre-Columbian chicken bones in Chile, and that they proved Polynesians had sailed to South America. (Storey et al, 2007) However, the dating and conclusion was called into question almost immediately by other scientists:

We disagree on two grounds. First, such indirect evidence is conjectural, documents no eastward expansion to South America, and says nothing about the prehistoric availability of particular mtDNA haplotypes. Second, our central point was that analyses of all available ancient (2) and modern chicken mtDNA data reveal that the El Arenal-1 chicken carries a worldwide genetic signature potentially available to any of the possible introduction routes via Europe, Asia, and Polynesia (3). In contrast, none of the unusual genetic signatures from Easter Island chickens have been reported from South America (3). The argument rests entirely on the radiocarbon dates. Current isotopic data indicate a fully terrestrial dietary signature (1). However, contrary to Storey et al. (1), El Arenal-1 is indeed a midden where chicken bones were found associated with marine organisms (4), and there are no local isotopic standards available to confirm the relationship between diet and isotopic signatures. Any marine input for the two new dates (1) would be consistent with a post-Columbian chronology. A region-specific set of isotopic standards and radiocarbon and stable isotope determinations for a large number of specimens of several species at the site are required as a matter of priority including dating additional chicken bones in independent laboratories to ensure reliable radiocarbon measurements. (Gongora et al 2007)

When the chicken bones are calibrated allowing for the marine-derived carbon the dates easily overlap the Spanish discovery and occupation of the Americas. (Gongora et al 2008) Which matches up nicely with Garcilaso’s statement that chickens were “among the first thing brought from Spain to Peru” (Garcilaso de la Vega, 1609, page 562) Not only is the original dating suspect, but the mtDNA analysis of the chickens show that:

The modern Chilean sequences cluster closely with haplotypes predominantly distributed among European, Indian subcontinental, and Southeast Asian chickens, consistent with a European genetic origin. A published, apparently pre-Columbian, Chilean specimen and six pre-European Polynesian specimens also cluster with the same European/Indian subcontinental/Southeast Asian sequences, providing no support for a Polynesian introduction of chickens to South America. In contrast, sequences from two archaeological sites on Easter Island group with an uncommon haplogroup from Indonesia, Japan, and China and may represent a genetic signature of an early Polynesian dispersal.

The chickens found in Chile and originally claimed to be of Polynesian origin, are the same types of chickens transported by the Spanish to the New World, and Polynesian chickens are shown to be west Asian in origin. Geoff Irwin, widely regarded as the expert in Polynesian seafaring, has stated that reaching America would have been at the outside limit of the Polynesian ability. (Terrell 2011) In this case, both the Incan and native chroniclers as well as science agree that the Spanish introduced the chicken to the Americas. While this writer is not opposed to the idea that the Polynesians could have used their extraordinary navigating skills to sail to pre-Columbian America, there is still no proof that this happened.

References

Acosta, Jose de, 1604 The naturall and moral historie of the East and West Indies … translated by Edward Grimston

Arriaga, Father Pablo Joseph de, 1621 The Extirpation of Idolatry in Peru, translated by L. Clark Keating 1968 University of Kentucky Press

Callaghan, Richard T. Prehistoric trade between Ecuador and West Mexico; a computer simulation of coastal voyages in Antiquity, Vol. 77 No 298

Garcilaso de la Vega, El Inca 1609, Royal Commentaries of the Incas and General History of Peru, Part One, translated by Harold V. Livermore, University of Texas Press, 1966

Gongora et al Reply to Storey et al, 2007, More DNA and dating studies needed for ancient El Arenal-1 chickens PNAS Vol. 105 No. 48

Gongora et al, 2008, Indo-European and Asian origins for Chilean and Pacific chickens revealed by mtDNA PNAS Vol. 105 No. 30

Hosler, Dorothy 1988 Ancient West Mexican Metallurgy, South and Central American origins and west Mexican transformations American Anthropologist, Vol. 90, Issue 4, pages 832–855

Lathrap, Donald W. The Antiquity and Importance of Long-Distance Trade Relationships in the Moist Tropics of Pre-Columbian South America , World Archaeology, Vol. 5, No. 2, Trade, pp. 170-186

Pease, Franklin 2008 Chronicles of the Andes in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries in Guide to Documentary Sources for Andean Studies 1530-1900 Vol. I edited by Joanne Pillsbury, University of Oklahoma Press

Seligmann, Linda J The Chicken in Andean History and Myth in Ethnohistory, Vol. 34, No 2, Spring 1987 pp 137-170

Storey, Alice A. et al, 2007, Radiocarbon and DNA Evidence for a Pre-Columbian Introduction of Polynesian Chickens to Chile, PNAS June 19, 2007 vol. 104 no. 25 pp.10335-10339

Terrell, John Edward, 2011, Review of Polynesians in America: Pre-Columbian Contacts with the New World Archaeology in Oceania Volume 46, Number 2