Waiting for Tartarus

Although Creighton never makes this point clear in his own discussion of the journal entry, 18th October was Vyse’s last full day in the harbour of Valletta on board the Edinburgh, before joining the steamer Tartarus bound for Alexandria.

If Creighton’s ability to read Vyse’s journal was of the level that he claims, why does he not explain to his readers that the Colonel was in Malta, which is stated quite plainly at the top of the relevant journal page?

Let us recall that Creighton’s reading of Vyse’s supposed entry for that date was as follows:

Wrote notes from the Quarterly Review abt: Rosellini & Champollion, our first books, 69 dollars 14.7.6. in half crowns. i

For a diary entry, this seems rather odd. Most obviously, if it is supposed to be a record of buying the books, why does it not say “Bought books by Rosellini & Champollion” or similar? Why so oblique, saying something quite different: that Vyse looked at The Quarterly Review and made notes? Why make a diary note saying that he had made notes about books that he had already purchased, or was proposing to buy? Why, if he already had the books, did he bother to mention The Quarterly Review at all? Furthermore, from this reading, Vyse would have used a lower case initial letter for the word interpreted by Creighton as “books.”

But, in fact, Vyse quite clearly begins that word – whether to be read as “books” or some other noun – with an upper-case B …

However, if Creighton’s reading is correct, why would Vyse have delayed until the very last day of a week’s quarantine in a foreign sea-port before locating and purchasing these expensive specialist works by foreign authors?

At this point, could we ask whether, despite Creighton’s best endeavours, ii he might have misunderstood Vyse’s (admittedly execrable) handwriting?

A close examination of the journal entry reveals the following alternative reading:

Breakfast, to Sir F. Hankey, ?received from him 87£ for Mr. ?C. ?L—pel ?sent in 1/2 ?crowns, ?sent Mr. ?Warder 25£ in a ? ?bag. ?D——d to repay him 2.1.8?p. ?sent in ?all. 18.15. for 10 dollars ?p. ?sent ?to ?Moritiy ?Wife, ?wrote ?to ?Sir ?F. Hankey, wrote notes from the Quarterly Review ab[ou]t: Rosellini & Champollion, ?& paid ?B–k[e]r 69 dollars 14.7.6. in half crowns, I dined in the Ward Room, & had a ?most ?hospitable ?dinner.

If this revised reading is correct, Vyse, having breakfasted, then visited Sir Frederick Hankey, the de facto Governor of Malta. Vyse received from Hankey the sum of £87.00 for (?) Mr. C … L … (?) (£87 being the equivalent of about £5,900 today). He then sent a Mr. Warder (?) the sum of £25.00 (the equivalent of about £1,700 today). There is a fleeting reference to a sum (a demand for repayment?) of £2/1/8 (about £140 today). The name “Moritiy” might refer to Vyse’s Maltese servant of that name, so perhaps Vyse was arranging a payment of 10 dollars (possibly representing about £170 today) for him via Mority’s wife: although, as with the rest of this journal entry, there might be several other readings and interpretations. iii

Money and Knowledge

But what also emerges from this alternative reading of Vyse’s journal, and what most crucially concerns us here, is the revised entry:

wrote notes from the Quarterly Review …

Again: it will be recalled that Creighton reads this as:

Wrote notes from the Quarterly Review abt: Rosellini & Champollion, our first books, 69 dollars 14.7.6 in half crowns.

But we believe that the phrase following the words“Rosellini & Champollion” is not “our first books,” but: “& paid ?B..ker 69 dollars iv 14.7.6 in half crowns …” v In this version, the upper case B (omitted in Creighton’s reading) more logically refers to a possible proper noun, a name, although the identity of the mysterious “?B..ker” (or perhaps even “?B…ber”) remains elusive. As no “Mr.” precedes it, the word might refer to a servant or subordinate, or purveyor of goods or services of some description.

The equivalent of £14/7/6 today would probably have been in the region of £900, vi just over half Creighton’s suggested figure of £1,650; but still a substantial sum paid over to “?B..ker”.

It is more difficult to find a present day sterling equivalent of 69 dollars; but possibly it represents somewhere in the region of £1,200. vii

Creighton, of course, argues that his reading indicates that Vyse was already researching the subject of hieroglyphic characters and the cartouche name or names of the king responsible for building the Great Pyramid. He reasons that Vyse, having read the long Quarterly Review article (of February 1835), had discovered that the article itself contained important indications about where to find more information about the name “Suphis” (as mentioned above, a variant of Khufu). viii According to this understanding of the situation, Vyse also went on to buy a book by Wilkinson mentioned in the article.

So does Creighton believe that Vyse had been inspired with the idea of setting off for Giza and inserting a forged cartouche name inside the Great Pyramid as early as February 1835?

Let us start by saying that we believe that – in part, at least – Creighton was quite right.

Vyse did look at the review (in fact, as we shall shortly see, he probably glanced through it once, and then read it with much more attention on a subsequent occasion). And he did buy a book by Wilkinson mentioned in that review.

Creighton maintains that the book in question purchased by Vyse – because, in Creighton’s opinion, Vyse believed that it contained more cogent information about cartouche names – was Wilkinson’s Materia Hieroglyphica (1828-1830). But the problem with this particular book, says Creighton, is that Vyse would have found that it lacked any images of the cartouche name “Suphis” – ix information that, of course, Vyse would have needed for the forgery that he was apparently planning even as early as February 1835, the publication date of the Quarterly Review.

So it was supposedly the lack of information in Materia Hieroglyphica that drove Vyse to acquire the relevant volume of Rosellini’s work: because I Monumenti contained “key information” about the cartouche name of Khufu. x

Although, as mentioned, Vyse did have with him one book by Wilkinson, there is unfortunately, a slight problem with the rest of this interpretation of what Vyse did.

Touring West, Gazing East

As is clear from Richard Seymour’s diary of 4th October 1835, Vyse’s abrupt decision not to return home seems to have come completely out of the blue as far as his family and circle in England were concerned:

Col:l V: is gone from [Kalisch?] alone to Egypt & Syria! could any thing be more strange – or more descriptive of an impetuous & unruly Spirit? xi

But what had impelled him to undertake this completely unexpected visit to the East? And why now? Is Creighton right when he suggests that it was the Quarterly Review article?

Let us go back to early August when, some time before the manoeuvres in Poland, the Vyses, father and son, had left England. What, one might wonder, had they been doing in all those weeks before the military spectacle?

Given that it was high summer, and that the pair were at leisure in an unfamiliar but picturesque part of the world, it might be reasonable to conclude that they spent some time touring round and sightseeing in such places as Hanover, Brandenburg and Berlin, before going on to Kalisch.

It might also be equally reasonable to conclude that Vyse had taken some reading material with him to while away the sultry Teutonic nights. So why not a work by Wilkinson, as covered in The Quarterly Review a few months previously?

But the book in question was not Materia Hieroglyphica. That was intended for a select scholarly readership, and would have had scant appeal for Vyse; xii he never refers to it, and there is no evidence that he had it with him. Nor could it have been Wilkinson’s best known work, Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians (which anyway did not become available until 1838). xiii

A clue is provided by the fact that the works by Rosellini and Champollion were not the first mentioned in The Quarterly Review piece.

Top of the list in the article in question xiv was in fact Wilkinson’s Topography of Thebes, also published in 1835; the very book – “which promises so much that it would be quite a treasure … ” – possibly discussed at breakfast with Gell in Naples two years before in 1833; the one book that definitely accompanied Vyse on his travels through the Middle East and all through Egypt. xv

Since Vyse was a wealthy and educated man interested in contemporary politics and ancient history, more likely than not he had subscriptions to many serious periodicals: amongst which such publications as The Eclectic Review xvi and The Quarterly Review xvii would surely have figured.

And, as mentioned, both periodicals reviewed Topography of Thebes.

Unfortunately, The Eclectic Review was not wholly favourable:

Mr. Wilkinson’s volume contains exceedingly valuable materials, but put together in an unworkmanlike manner. His arrangement is by no means clear; his transitions are ill-managed; and there is an awkwardness about his style …

Damning with faint praise, the reviewer continued:

[W]ere we setting forth on a steam-trip to the dominions of Mohammed Ali, we should assign to it the first place in our travelling library … xviii

But The Quarterly Review was more encouraging:

Those … who wish to obtain a more rapid and compendious view of the progress made in Egyptian discovery will consult the volume of Mr. Wilkinson …

We propose that Vyse, having read, or at least glanced through, these reviews, noted that the book by the author whom he had discussed with his friend back in Naples had now been published, and obtained a copy which he took with him when, later in the year, he left England to visit Kalisch.

The Quarterly Review had finished on a more upbeat note than The Eclectic Review:

To future travellers in the East this book will be an indispensable manual. xix

Indeed, the book was essentially a tourist guide, with some brief descriptions and discussion of both pyramids and the subject of hieroglyphs; the sort of work that might inspire a rich and well-read man to see for himself the wondrous sights and architecture of a semi-mythical land mentioned in the Bible, and just opening up to visitors from Europe and America. As the military review of Kalisch was breaking up at the end of September 1835, perhaps Vyse leafed once more through Topography and came to a decision.

Whiling away quarantine

A year later, on 1st October 1836, Vyse left Vourla, on the eastern coast of Greece, on board the Edinburgh, reaching Valletta on 11th October, where he was obliged to stay until the end of the quarantine period. Then, on his last day, he made the mysterious (and near-illegible) entry in his journal that we believe says:

… wrote notes from the Quarterly Review ab[ou]t: Rosellini & Champollion …

We know that Vyse could have purchased books by both Rosellini and Champollion while back in England (or, in the case of the one by Rosellini, while he was in Italy). But, although Vyse refers to Champollion in his published work, xx there is no evidence that he had copies of books by either author with him in Egypt. We have seen that the evidence points to him having Topography in his possession; but there is no reference to anything else.

Could he have purchased copies of these two specialist works while he was staying in Valletta? As it was a busy port city, the capital of Malta, it could well had several bookshops selling local publications and imported works, particularly from Britain and Italy.

And, if indeed Vyse ,on his last day in Malta, had managed to find and purchase specialist works by Champollion and Rosellini, what might he have paid for them?

In 1833, the first two parts of Rosellini’s Monumenti dell’Egitto e della Nubia were advertised in Paris for ff46 – xxi the approximate equivalent today of £125. (Presumably, mark-ups would have been applied to sales of this work in foreign countries.) Five years later, by way of comparison, Wilkinson’s Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians was on sale in London for 3 guineas (£3 3 shillings); xxii the equivalent of about £200 today, the sort of price that might sometimes be paid now for a scholarly work. xxiii

We have seen that Vyse did not mind supporting worthwhile expenditure on, or contributions to, fields of scholarly endeavour. But why this sudden concern with Rosellini and Champollion, pioneers in the field of understanding hieroglyphic characters? And why on his last day in Valletta? Was this because, as Creighton suggests, Vyse was indeed now moving forward with his plans to insert forgeries of the cartouche name of Khufu inside the Great Pyramid, despite never having seen anything more at this stage than a few rubble-filled passages?

iCreighton 2021: Appendix 1.

ii He has discussed in some detail his ability to read the MS, e.g., in this online forum at #274.

iiiWhilst the nature of Vyse’s payments and receipts are not at all clear, it should be borne in mind that Valletta was a commercial and banking centre of some importance at this time (Henry Frendo, “Ports, Ships and Money: The Origins of Corporate Banking in Valletta”; Journal of Mediterranean Studies Vol. 12, No. 2, 2002, [327-350], a place where (perhaps sometimes quite complex) financial transactions could be effected, especially if (like Vyse) one had been travelling for some months with little opportunity to attend to financial affairs. (In the late 1870s, his daughter-in-law describes obtaining money (35) from a Jewish banker in Essaouira, Morocco.) It might also be borne in mind that Vyse was heading for Alexandria, where the banking concern Briggs & Co., presided over by the British Consul, Robert Thurburn (1784-1860), had their offices; possibly some of the sums of money listed in Vyse’s journal were intended for people or organisations connected with those offices, but, in the absence of firmer evidence, this proposal must remain tenuous at best.

ivPossibly Spanish Dollars, widely used in global trade at this time.

vImage of William IV 1836 half-crown.

viSee National Archives Currency Convertor.

vii Governor Bannerman and the Penang Tin Scheme. 1818-1819 – C. D. Cowan, Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. 23, No. 1 (151) (February, 1950), pp. 52-83; 55, n. 4. Or was Vyse saying that he paid someone the sum of $69 (Sp.) in its sterling, half-crown, equivalent of £14/7/6? Again, this question must remain open.

viii 1835 (Feb-April): 61. (The citation in Void: Ch. 8. gives “115”.)

ix However, as well as the Khufu cartouche, the relevant plate in Wilkinson’s work in fact also contained the Khnum-Khufu cartouche, and a variant writing of the name Khufu (1828; 1830: Unplaced Kings; Plate V: b, e, M).

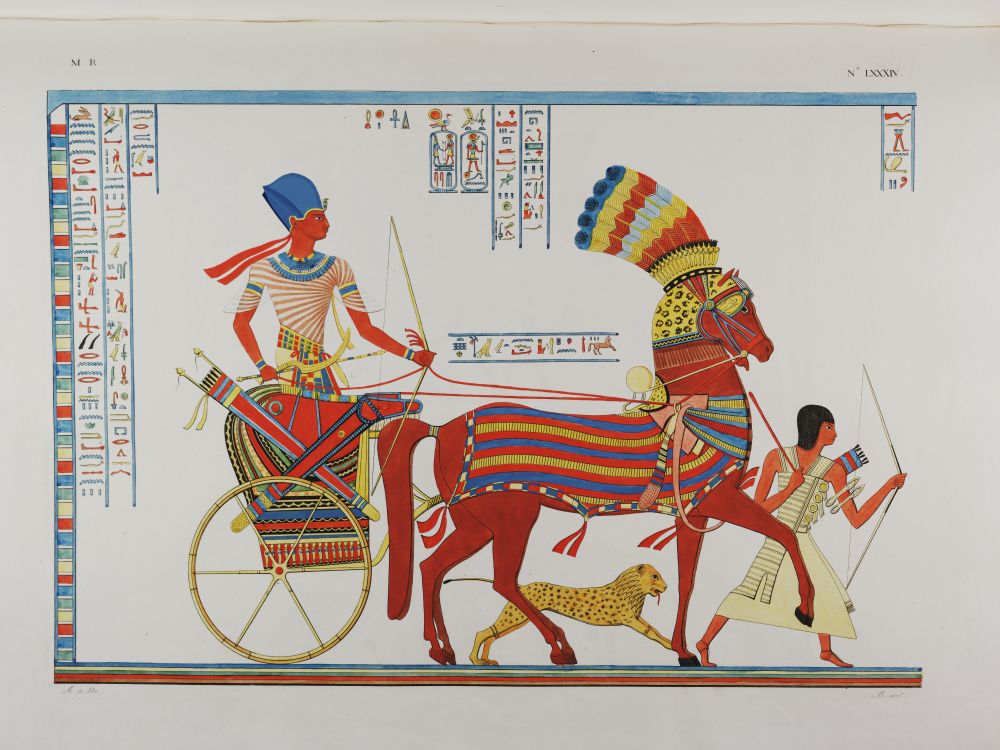

x 1832: Part 1, Volume 1. Vol. 1 (Pt 1): 128-130.

xiSeymour, Richard. 1832-1911. Diaries of Richard Seymour and Poems of Hester E. Seymour (WRO Acc. No. MI296). 16 vols. (And see also https://smithandgosling.wordpress.com/, passim).

xiiFor further discussion of Materia Hieroglyphica, see Stower, Martin; Coburn, Jean. The Strange Journey of Humphries Brewer: Witness to a Forgery in the Great Pyramid? Part 1: Investigating the Legend (p. 147).

xiii The Times, 24 Jan 1838, Issue 16634, 8. There are two advertisements: one stating that the work is now available “this day,” and the other stating that it will be available “Wednesday next.” See also The Examiner, 29 Oct 1837: “New Books on the Eve of Publication.”

xivLondon Quarterly Review. 1835; Feb-April: 54-76. Art. V. “Egypt and Thebes (Reviews of Wilkinson’s “Topography”; Rosellini’s “Monumenti”; Champollion’s “Lettres d’Egypte”; Wilkinson’s “Materia Hieroglyphica”; Klaproth’s “Examen Critique”; Salvolini’s “Des Principales Expressions”).

xvFor instance, Vyse writes: “I found Mr. Wilkinson’s book particularly useful at Karnac”; detailed descriptions of Karnak appear in Topography, 171-2. Vyse’s comments about numbered tombs in Operations I: 85-86, meanwhile, clearly refer to the corresponding section in Topography, 109. Wilkinson also includes a brief description of the Great Pyramid (324-7).

xvi The Eclectic Review, vol. xiii, Jan-June 1835: 448. Lettres écrites d’Égypte et de Nubie en 1828 et 1829, Champollion the Younger. Examen critique, Klaproth.

xvii Its conservative political stance would presumably have found particular favour in his eyes..

xviii The Eclectic Review, vol. xiii, Jan-June 1835: 449. The author of the review was perhaps Josiah Conder.

xix 77.

xx E.g., at Ibrim: “Some of these hieroglyphics are published in M. Champollion’s works” (51, n. 4). Possibly this text, from Champollion, Lettres écrites d’Égypte et de Nubie en 1828 et 1829, as reviewed in the Quarterly Review (February 1835).In Ops. I: (App. N. III), 160-1, n. * is a reference (which could not be precisely located) to Champollion, Monuments de l’Égypte et de la Nubie. Ops 2: 138, n. 6 refers to the name “Soutefmau” in Champollion, Grammaire égyptienne ou Principes généraux de l’écriture sacrée égyptienne appliquée à la représentation de la langue parlée: 282; but this is from a section by Samuel Birch.

xxihttps://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6202107j/f867.item.r=RoselliniMonumenti%20dell’Egitto

xxii The London Times, 24 Jan 1838, Issue 16634, 8.

xxiii E.g., Archaeology and Geology of Ancient Egyptian Stones (Harrell).Open publish panel

1 thought on “The Strange Journey of Howard Vyse – Part IV: Last Day on HMS Edinburgh”