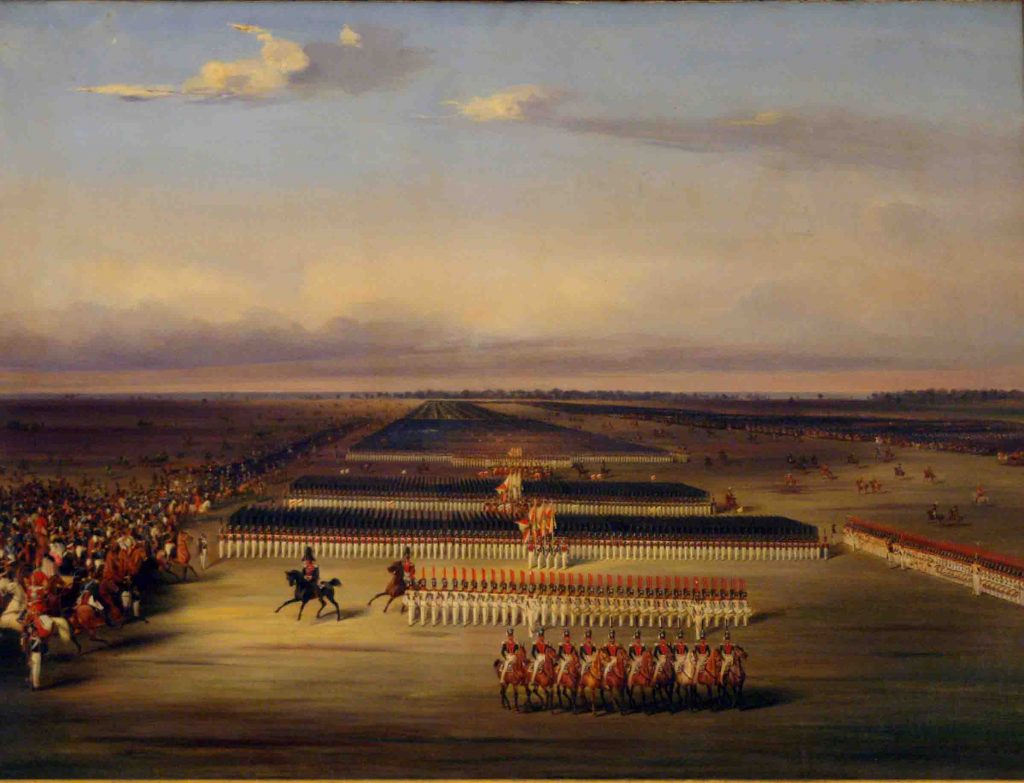

Prussia shows its Strength

Some years earlier, in 1830-31, there had been a Polish uprising against Russia. Having thoroughly quashed the revolt, Russia decided to display its might to the rest of Europe, along with Prussia, a country with which it had continuing ties. Under King Frederick William III, Prussia had a very large army, and was one of the most powerful and ambitious states within what was known as the German Confederation. i

It was arranged that, from 12 to 22 September 1835, ii a military review, with 60,000 troops from the Russian Imperial Army, should be held in Kalisch, an important city in central Poland (Poland itself was by then little more than a puppet state of Russia).

By the side of mighty Prussia, the kingdom of Hanover was just a minnow. Its army was smaller. Its foreign policy was sometimes complicated by the fact that it shared the same monarch as the United Kingdom, at this time, William IV, represented at Kalisch by his brother, the Duke of Cumberland. But, although Cumberland represented both British and Hanoverian interests at Kalisch, he (somewhat confusingly) wore a Prussian uniform. iii

The Duke was accompanied by the usual retinue, including equerries – one of them, of course, being Howard Vyse, who, travelling via Rotterdam, left England together with his son, Richard, on 8th August, iv nearly a month before the Duke, v and some five weeks before the start of the manoeuvres.

In the spring and summer, and during the months leading up to September, excited commentary and speculation about the forthcoming review began to appear in the press. A correspondent of The Times writing from Berlin in mid-August stated that:

A very handsome residence has been hired and fitted up for the English Ambassador Extraordinary, who is expected about the end of this months, and will afterwards go to Kalisch and Toplitz. We are able to state on good authority that His Majesty the Emperor Ferdinand [of Austria] has invited all the reigning Princes of the German Confederation to Toplitz. vi

In his memoir, politician Lord Teignmouth provides a vivid description of the events at Kalisch, and some of the personages there. vii Although no real fighting was supposed to take place at the review, there were some bad accidents and at least one fatality. For his part, Teignmouth exchanged pleasantries with various people, including the Duke of Cumberland, before leaving for a private tour in about the third week in September, when the military review was nearing its conclusion.

By this time, of course, many of the rest of the great personages were already heading to Toplitz, in Austria, where, in early October, as mentioned above, there was to be much serious political discussion; viii obviously, anyone who was anyone would have wanted to go, so it was surprising that a large number of the less important princes of the German Confederation were apparently refusing to travel there. ix But someone as important as the Duke of Cumberland would automatically have a place at the top table.

At least, so one might have thought.

Cumberland, it will be recalled, was representing his ailing brother, William IV, who, besides being King of England, was also King of Hanover. When William died, someone else must of course succeed to the English throne. Because of differences between the laws of succession of England and Hanover, the next occupant of the English throne would likely be Princess Victoria, while the next occupant of the Hanoverian throne (who, under the laws applicable in Hanover, could not be a woman) would be Victoria’s uncle, the Duke of Cumberland. But, of course, if anything prevented Princess Victoria’s accession – and there had already been some rumours and rumbles to this effect – the Duke of Cumberland could theoretically have been King of England as well.

At this juncture, therefore, Cumberland might have been viewed as a future monarch of at least one country, and possibly two, so someone of potential significance in the European landscape. Certainly, as he made ready to wend his august way to Toplitz, all the signs were that that was how he viewed himself.

Unfortunately, as explained by diplomat Sir Robert Adair to the Foreign Secretary, Lord Palmerston, there was one slight problem. Despite the report in The Times about all German Confederation princes being invited to Toplitz, Cumberland himself hadn’t actually received an invitation to the gathering, and haughtily refused to go through what he evidently considered to be the undignified process of sending a courier to Vienna to request one. Unperturbed, he set off in company with Lord Roden and the Duke of Gordon (themselves also not very popular for various reasons); but, as Adair remarked, the three men’s unseemly scramble to join the gathering at Toplitz had struck him as:

… merely a “foolish proceeding of the above parties in order to give themselves an air of being in communication with foreign kings and ministers … ” x

Adair obviously had the measure of the situation; for, when Cumberland turned up at Toplitz, he found himself sidelined, cold-shouldered, and shrivelled by icy stares from the likes of the Austrian Chancellor, Metternich. xi

But what of the Duke’s equerries: in particular, Colonel Howard Vyse and his son? Had they braved the embarrassing absence of invitation, and loyally followed their leader to Toplitz?

Back in England, George and Lizzy, and their friends and relations, had of course been anxiously awaiting word from George’s father on a personal matter that probably meant far more to them at that moment than the future of European politics being weightily discussed in Poland and Austria.

On 4th October, Richard Seymour recorded in his diary that there had come news, of a sort.

George’s brother, Richard, had returned from Poland: but without their father.

***

At the end of September, Vyse had found himself on the horns of a dilemma. Clearly, his family were expecting him and Richard to return to England when the military review was over; equally clearly, his duty as an equerry to Cumberland, and loyalty to his long-time patron, might have been beckoning him on into the Ninth Circle of Hell at Toplitz.

And there was also another, although less immediate, difficulty. William IV was in a poor state of health, and had been so ill a few months previously that his brother had hot-footed it from Germany to visit him. Everyone knew that the question of the succession must at some point come to the fore. Would Cumberland’s niece, Victoria – of whom very little was known at this time – become Queen? Or, if something happened to prevent this, might her uncle, the Duke, become King in her place? Given Cumberland’s public standing, such an event might well have provoked a great deal of popular agitation.

In the early 1830s, we have seen that Vyse might have found it convenient to withdraw to Italy because of the social unrest back in England.

Might he have found it equally convenient in 1835 to again use foreign travel as a means of avoiding being caught up in any further social upheaval in England following any future problems with the eventual succession? Might Vyse have been alarmed by some of the talk he heard at Kalisch? What would he do if there were ever to be some kind of confrontation between the parties attached to the two monarchs-in-waiting? xii His loyalty lay with the Duke; but his duty as an obedient British subject, descendant of the Archdeacon of Lichfield, and defender of the throne, must surely lie with Princess Victoria.

He seems to have come to a snap decision. No matter what might be Cumberland’s demands on his family’s loyalty, Vyse could not be seen to be involved in any attempt to put him on the throne. He would distance himself from Cumberland’s appalling public image and the endless embarrassments and trouble he left in his heedless, heavy-footed wake, and travel on alone to distant parts in pursuit of his well-known love of antiquarianism. So, bidding farewell to the astonished Richard, and to Cumberland and his travelling companions, he left Kalisch.

It would be another two years before he saw Stoke Place again.

First Sight of the Pyramids

In Operations, Vyse explains how, some three months later, on 29th December 1835, he fetched up at Alexandria, intending to visit Upper and Lower Egypt. But his initial tour of Giza, and his meeting with the Italian explorer, Caviglia, in February 1836 (I: 12), introduced to him the stunning reality of the pyramids – although, at that stage, Caviglia was not interested in the Colonel’s offer of financial help with their exploration. Dismissing the matter from his mind, Vyse left to tour Syria and Asia Minor, returning to Alexandria in October 1836, some nine months after his first arrival at the port city at the end of 1835.

So, according to Vyse, he had spent most of 1836 in pursuing matters other than the pyramids at Giza and elsewhere. If, as argued by some, he was already considering inserting a forgery in the Great Pyramid, he seems to have taken rather a long-winded and roundabout way of going about it.

Let us take a closer look at that itinerary and that date, as recorded in Vyse’s own words:

I again arrived at Alexandria on the 25th of October … xiii

Vyse was just returning from a tour in Syria and Asia Minor. The most probable means of travel to Alexandria was by sea. And yet, only a week before Vyse’s disembarkation there, Scott Creighton argues that Vyse’s journal states that he bought expensive books, and made detailed research notes from a journal published some eighteen months previously.

Let us go back to Creighton’s note of Vyse’s journal entry:

… in his private journal entry of October 18, 1836, Vyse writes the following short passage …

Interestingly, although Creighton provides no indication of Vyse’s whereabouts on 18th October 1836 in his book, he does state in an online forum that he knows that Vyse was “enroute [sic] for Egypt.”

So where exactly was Vyse when he wrote his journal entry for that day? If he was not actually at sea, where was he?

Some pages in Vyse’s private journal earlier that year record his (not uneventful) trip to Syria (27th April and 12th-14th May 1836). xiv On 1st June 1836, Vyse noted that: “I gave a passage to Smyrna to Mr Purser, the Artist” (presumably William Purser); it seems that Purser and Howard Vyse travelled together during June, or perhaps longer. xv In later pages from October 1836, it emerges that Vyse’s travels had eventually taken him to Turkey, which he left on 1st October on board the HMS Edinburgh. On 11th October, the Edinburgh reached the port where Vyse was obliged to spend a week in quarantine. xvi

That port was Valletta, the capital of Malta.

Painter: JMW Turner (1775 – 1851), public domain. MUŻA – Mużew Nazzjonali tal-Arti u l-Komunita’. http://www.heritagemalta.org/

iThis consisted of just under forty German-speaking states in Central Europe. The confederation had been established after the Congress of Vienna in 1815.

iiAlthough, in the event, the dates did not quite adhere to this plan.

iii Reminiscences of Many Years, Teignmouth, Charles John Shore, 1878, vol. II: 156, n. 1.

ivMorning Herald, Monday 10 August 1835. Vyse had left on the Saturday [8th August], bound for Rotterdam, two days after Richard Seymour had suggested [6th August] that George write, rather than speak, to his father about the vexed question of George’s marriage with Lizzy.

vThe

Duke of

Cumberland set off yesterday morning, at an early hour, for his

residence at Berlin (The

Times,

Saturday, Sep 05, 1835; pg. 3; Issue 15887). A

week later, having reached Berlin, he set off for Kalisch.

The

Times,

Monday, Sep 21, 1835; Issue 15900; pg. 1.

vi Aug. 22, 1835, Issue: 15875: p. 5.

vii Teignmouth 1878, vol. II: Ch. 7.

viii The Times, Thursday, Sept. 24, 1835; Issue: 15903.

ix The Times, Monday, Sep 21, 1835; Issue 15900; pg. 1.

xAdair to Palmerston, 30 Sep 1835.

xi Adair to Palmerston, 7 Oct 1835.

xii There were genuine fears that Cumberland, backed up by some disaffected elements, might stage a coup.

xiii Ops. I: 13.

xiv David Kennedy: Newly Discovered Western Travellers to Palmyra in 1836.

xv David Kennedy: An Unknown British Couple at Jarash and Palmyra before 1837. ‘Mr and Mrs Smith’?; and n. 5.

xvi D121 6: Pg. 8 [203].

You may also like

-

The Strange Journey of Howard Vyse – Part V: Finally … Pyramids

-

The Strange Journey of Howard Vyse – Part IV: Last Day on HMS Edinburgh

-

The Strange Journey of Howard Vyse – Part II: The Duke of Cumberland

-

The Strange Journey of Howard Vyse – Part I: Origin of a Forgery Plan

-

Surid Missing his Mummies